Why it’s so hard to fuel the Artemis rockets

Liquid hydrogen fuel leaks forced NASA to delay the launch of Artemis II—the same scenario it encountered four years ago during the Artemis I mission.

This past week, NASA called off its February launch attempts for Artemis II, it’s first crewed mission to the moon since 1972, after issues arose during a fueling and countdown “dress rehearsal.” Now, pending fixes, the earliest Artemis II can launch is March 6, 2026.

The issues flagged during dress rehearsal included communication dropouts between ground teams, cameras impacted by cold weather, a pressurization valve for the crew capsule hatch, and, notably, liquid hydrogen fuel leaks while loading propellant into (or “tanking”) the rocket. “All in all, a very successful day for us on many fronts,” said launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson at a press conference. “Then on a couple of others, we’ve got some work we’ve got to go do and we’re going to do it. We’ll figure it out”

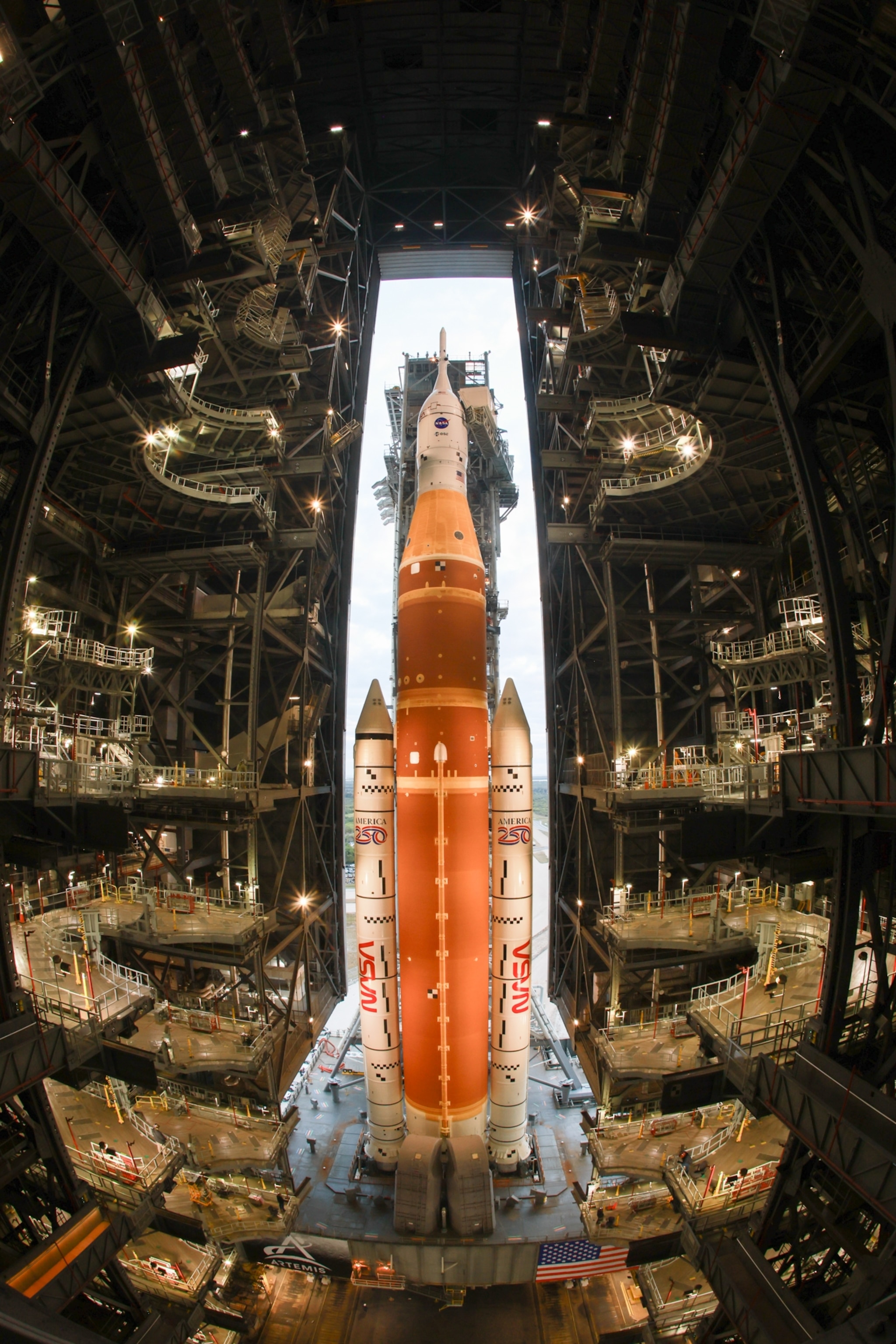

If those hydrogen leaks sound familiar, it’s because Artemis I had the exact same issue. Almost four years ago, in April 2022, NASA called off the third launch rehearsal for Artemis I because of liquid hydrogen fuel leaks. The agency ended up rolling the Space Launch System (i.e. the SLS) rocket back to its assembly building to make repairs, and Artemis I didn’t launch until months later in November 2022. Even then, during the actual Artemis I launch countdown, a crew was sent to the launch pad to tighten a bolt because of a leaky valve.

“With more than three years between SLS launches, we fully anticipated encountering challenges,” NASA administrator Jared Isaacman wrote on X. “That is precisely why we conduct a wet dress rehearsal. These tests are designed to surface issues before flight and set up launch day with the highest probability of success.”

But why is NASA encountering the exact same issues with the rocket that it did four years ago—issues it has already troubleshooted over many years? To understand that, it’s helpful to learn the history of SLS and the finicky nature of liquid hydrogen.

Liquid hydrogen fuel is hard to work with

SLS uses two types of propellant: liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. Liquid oxygen is relatively easy to work with. Liquid hydrogen, however, is not.

It’s particularly prone to leaking because it’s such a small molecule, capable of escaping through the tiniest equipment gaps. It also must be kept at extremely cold temperatures (-423 degrees F) to stay in liquid form. In turn, that extreme cold can then affect the integrity of the seals, leading to increased leak rates.

Many modern rocket companies—like SpaceX and Blue Origin—are moving away from liquid hydrogen for these reasons, pivoting their fuel to a blend of liquid methane and liquid oxygen, which isn’t as leak prone and can be stored at higher temperatures (-295 degrees F).

However, liquid hydrogen also has its benefits: It’s environmentally friendly (the byproduct of liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen is water) and is very efficient.

But for NASA, there wasn’t much of a choice to use alternative fuel sources for SLS. When Congress authorized the Space Launch System back in 2010, they mandated that the rocket be based on heritage space shuttle technology. That means that the RS-25 engines that power SLS are simply upgraded and refurbished engines from the space shuttle, which required liquid hydrogen fuel. Three of Artemis II’s four engines are previously flown space shuttle engines; one is new. The space shuttle also had problems with leaks during its operation—the final flight of the Space Shuttle Discovery was delayed due to hydrogen leaks .

This decision was initially made to save money on SLS, but it hasn’t worked out in practice. In 2023, the NASA Office of the Inspector General estimated the cost of SLS has ballooned to around $4.2 billion per launch. (NASA’s retired space shuttle program, which also grew more expensive than its designers intended, cost around $1.5 billion per launch.)

The good news: NASA did manage to fully fuel SLS

For most of the dress rehearsal, the fueling test actually went quite smoothly. When a leak was detected soon after propellant loading began, the team was able to deploy a technique refined during Artemis I, and warm up a key seal before continuing.

But then, another issue arose. Because the super-cold hydrogen fuel heats up after loading, and actually boils off, it must continually be replenished. An increase in leak rates during this replenishment then led to the rehearsal being called off at T-5 minutes.

Now, teams must identify exactly which seal is leaking and make repairs to it while the rocket is out at the launch pad, which is not an easy task. “We have to go inspect the seal and see what condition it’s in,” said Amit Kshatriya, NASA associate administrator, at a press conference this week.

NASA is implementing procedures developed during Artemis I to conduct this work without rolling the rocket back to its assembly building in hopes of making those March launch dates. Then, after adjustments are made, the agency will have to attempt and complete a second rehearsal before clearing SLS to fly.

The bottom line is that despite being built on legacy technology, SLS has only flown once before, and NASA is still learning as they go.