To explore space, scientists want to turn the moon into a gas station

Using lunar ice to make rocket fuel could help future lunar settlements sustain themselves and provide a launch pad for astronauts to reach Mars.

One way or another, humans are returning to the moon. And this time, they’re staying—both the United States and China plan to build their own lunar bases on the lunar south pole. That location isn’t random; it’s thought to contain reserves of precious water, either in the form of ice, buried water, or both. Those reserves could be used to hydrate astronauts, grow crops, and make rocket fuel.

That last application may sound surprising, but the chemistry is pretty basic. Water is made of hydrogen and oxygen. When liquefied, both of these elements can ignite and be used to very effectively propel spacecraft.

If this alchemy works on the moon, then that would make the lunar south pole more than just a scientific research post. It would become a fuel depot, one that could manufacture its own propellant rather than having it expensively sent over from Earth. And that would make getting to Mars considerably easier.

“The benefits of abundant propellant produced on the lunar surface are enormous,” says George Sowers, a mechanical engineer at the Colorado School of Mines. “Water is the oil of space.”

None of the technology needed to turn water into fuel comes from science fiction; it all exists in one form or another already, but it’s only ever been properly used on Earth. The low gravity, extreme nature of the lunar south pole is quite a different setting to our own planet. “We have no clue if it’ll work under these conditions,” says Paul Zabel, a researcher at the DLR Institute of Space Systems in Bremen, Germany. And there’s only one way to find out.

(Everyone wants a piece of the moon. What could go wrong?)

Water divining on the moon

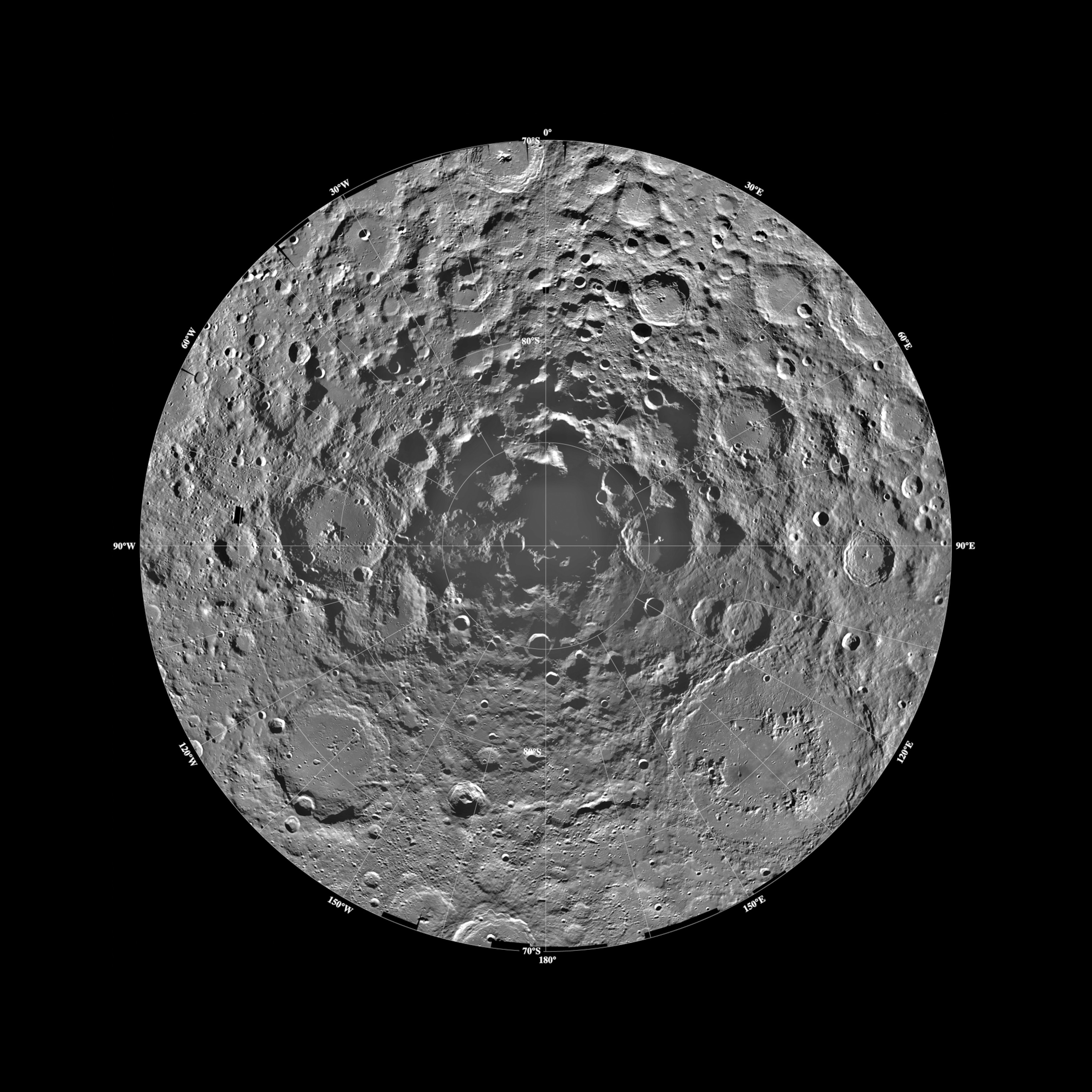

The first step will be figuring out where the moon’s water is hiding. Astronauts have yet to recon the lunar south pole themselves—and although evidence from orbiting probes from both NASA and India’s space agency has determined that it does contain water, there might not be an abundance of it.

When hit by sunlight, the lunar surface can hit 250°F, while in darkness, it can plunge to -410°F. Even in particularly cold parts of the Moon, any ice gets vaporized and escapes into space, as there is no atmosphere to keep it on the surface.

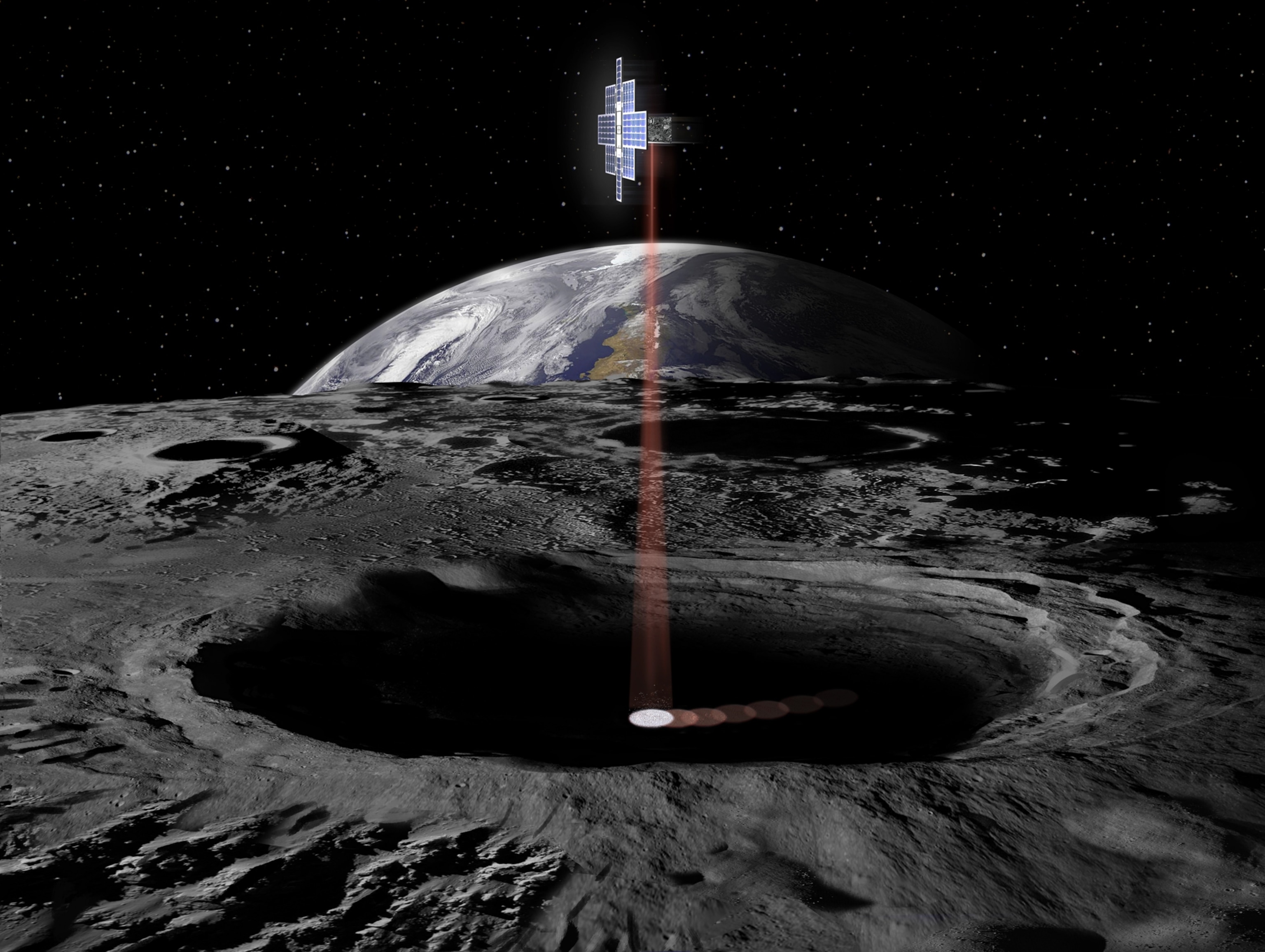

Some of the most promising sites are known as permanently shadowed regions, parts of the lunar surface—often steep, deep craters—that are never exposed to sunlight and are some of the chilliest places in the universe. These areas “are the best chance of finding large quantities of water that can actually be used for resources,” says Julie Stopar, a senior staff scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute.

But within those benighted chasms, don’t expect to find glaciers. “The water isn’t really there as an ice rink. It’s mixed into the soil,” says Stopar. “There’s some evidence of surface frost, but that’s not going to be a huge volume.”

Even if those craters of perpetual darkness are brimming with water, they would be highly precarious places for astronauts to explore, even with high-tech lunar rovers transporting their scientific and mining equipment along for the ride. “It’s questionable if we can go in there with a rover at all,” says Zabel.

(What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?)

Cooking up moon rocks

If, however, water in the lunar soil is accessible and plentiful enough, then it can be extracted. And there are multiple ways that engineers have proposed to accomplish this—most of which involve heating the rock to expunge the water trapped in it.

“If there is enough ice near the surface, then heat can be applied to the surface directly and the vapor captured under a dome called the capture tent,” says Sowers. The vapor is then collected in a chilly container called a cold trap , where it turns into usable ice.

Despite being one of the coldest places in the cosmos, the moon’s surface may one day have multiple heat sources. Reflected sunlight is one option. Alternatively, both the U.S. and China also plan to put nuclear reactors on the moon so that they aren’t reliant on using solar power—which can be somewhat fickle on the lunar south pole—to sustain their bases. The fission reactions that would split atoms to power those plants also produce excess heat that could be harnessed for water extraction.

In recent years, space agencies and industry partners have come up with different ways to use heat to retrieve lunar ice. One proposal would deploy a rocket engine, trapped under a pressurized dome, to carve out deeper craters and extract more water than other methods would allow. Although focusing more on Mars, NASA also has their own “dust-to-thrust” concept where autonomous robots would dig up extraterrestrial soil, transport to a processing facility, and heat it up with ovens to remove the water.

One of the most promising water extraction technologies comes courtesy of a European Space Agency project named LUWEX (short for Lunar Water Extraction)—and a working prototype already exists. Either autonomous mining robots or astronauts would dump icy soil into the contraption’s mouth. Zabel, the LUWEX project manager, explains that heating up frozen lunar rocks is quite difficult, because of the lack of an atmosphere on the moon and the already frighteningly low surface temperatures. That’s why LUWEX’s crucible stirs and rotates the lunar soil, which broils it more efficiently and removes the ice.

From there, a cold trap captures the liberated water and transfers it into a liquefier, ready to be used. Well, almost ready: At this stage, the water is still polluted by extremely fine, glassy-like pieces of lunar dust. “It has a kind of milky appearance—like grey milk,” says Zabel. Fortunately, engineers working on the project have also designed a purifier than seems to work wonders. “We achieved drinking water quality.”

Zapping water into flammable gases

Finally, the water then needs to be split into hydrogen and oxygen through a process known as electrolysis, where electrical currents essentially break the molecular bonds between these two elements.

There are multiple versions of this process that work on Earth. Space has seen fewer demonstrations of this technology, but several labs have tested it out in super-cold vacuums—a simulation of the lunar surface. And NASA’s Perseverance rover’s MOXIE experiment showed that you can use electrolysis to split breathable oxygen away from toxic carbon dioxide on Mars.

But even drinkable water isn’t good enough to be electrically split into hydrogen and oxygen; there are still too many chemical impurities in it to produce a clean fuel. For LUWEX, “we would need to add another polishing step,” says Zabel. He notes that extremely effective water purification technologies are commonplace on Earth. “It just needs to be transformed into technology for space.”

Then, when you have your crystal-clear water, you can extract your hydrogen and oxygen gas from it by zapping it. “Finally, the gases are liquified and stored as liquid hydrogen, liquid oxygen propellants,” says Sowers.

Zabel hopes that in a few years, LUWEX will find its way to the lunar south pole. “It would be nice to produce one litre of water on the Moon as a technology demonstration,” he says.

(The farthest journey in human history is about to begin.)

Cheap gas may drive the next space race

We’re still a long way off from having what are effectively gas stations on the lunar south pole. But if the space race between China and the U.S. really heats up, as it’s expected to, then rapid technological development won’t be far behind.

“There’s a lot of great engineering, and a lot of great ideas,” says Stopar. “Somebody needs to take that first step.”

When the first lunar bases are set up, and astronauts spend more than just a few days or weeks there at a time, most of what they will need to survive will be shipped from Earth. But over time, these bases will need to become self-sustaining—because launching anything off Earth costs a huge amount of money, because of our planet’s strong gravitational pull and the need to use vast amounts of rocket fuel to escape it.

But the Moon has low gravity, and no atmosphere to punch through. So launching rockets from there is easier—and cheaper—than jettisoning anything off Earth.

Why not use the lunar south pole as a staging ground for future solar system exploration? Largely because this would require considerably less fuel overall, “the cost of a single human Mars mission can be reduced by $12 billion using lunar propellant,” says Sowers.

It won’t just be rockets that would use this water-forged propellant either. You could “put them in fuel cells to power rovers,” says Zabel. You could use them to sustain much more energy-intensive machinery that either can’t be reliably powered by solar cells or safely powered by nuclear fission reactors.

And what will work on the moon will also likely operate elsewhere too. Making the lunar surface a self-sustaining environment will be helpful. But for astronauts to stay on the Red Planet, this sort of system will be essential. “The whole Moon-to-Mars architecture does rely on some of that being demonstrated on the lunar surface,” says Stopar.

But even if it does become possible to mass-manufacture drinkable water and, in turn, rocket fuel on the Moon, that leaves one rather awkward problem with no clear solution. “The resources are not infinite,” says Zabel. It’s easy to imagine a situation in which China and the U.S. are racing to find, and mine, that invaluable water before each other, in the same cramped corner of the Moon.

“There might be a conflict at some point,” says Zabel.