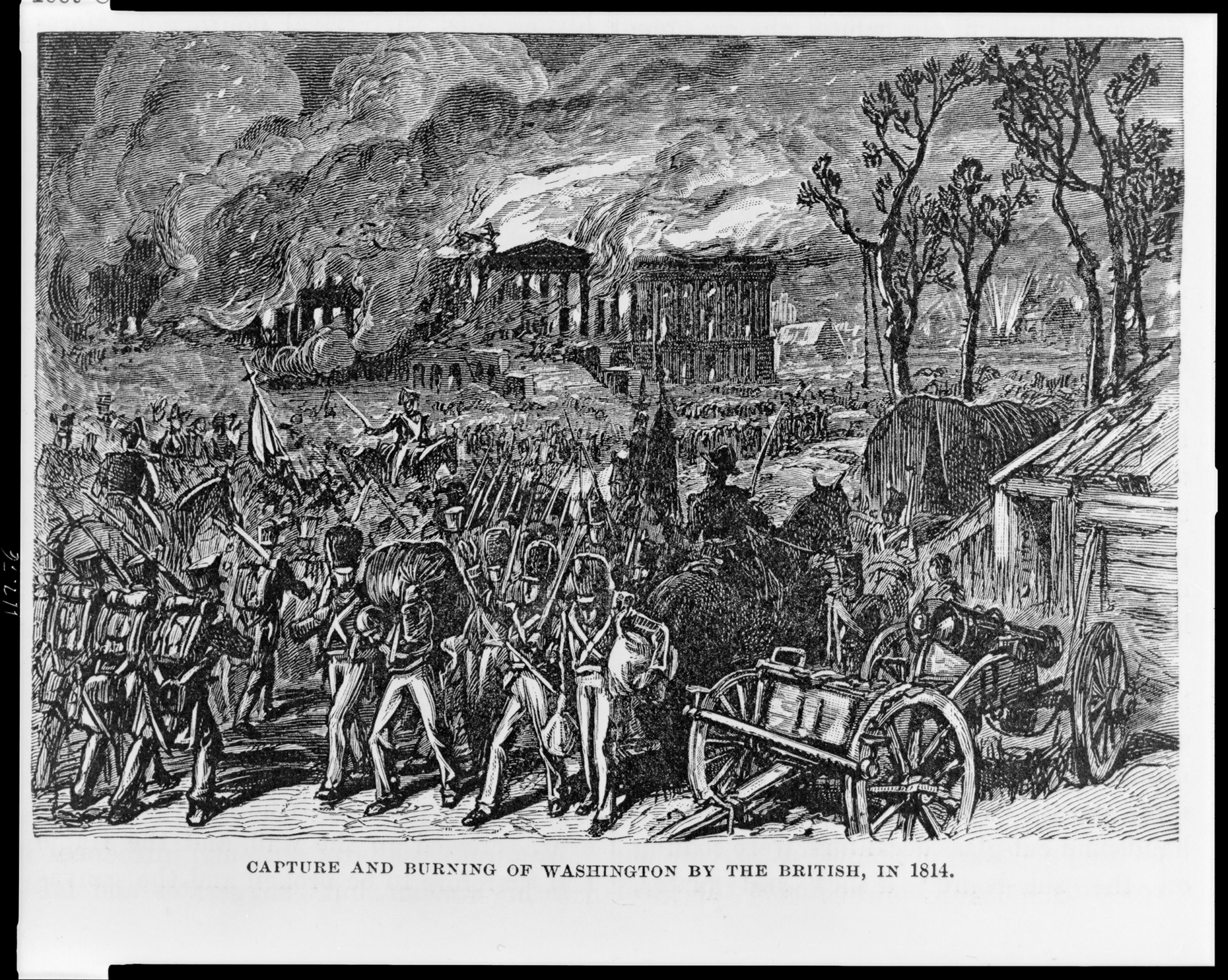

Remembering When White House Was Burning, President Was Hiding, and U.S. Was Close to Collapse

200 years ago today British troops seized control of Washington, D.C.

The United States and Britain now enjoy a "special relationship," but on this day in 1814, a force of battle-hardened British troops overran a poorly armed American militia, seized control of the city of Washington, and set the White House ablaze. It was the worst military defeat ever suffered by the U.S.

Using previously unpublished eyewitness accounts from both sides, veteran British broadcaster Peter Snow has reconstructed the fateful events of August 1814. Here he talks about why the two sides went to war, what Presidents James Madison and George W. Bush have in common, and what President Obama said to Prime Minister David Cameron when he visited the White House.

Today is the 200th anniversary of one of the darkest days in American history—the burning of the White House by the British. How does that event compare in its psychological and political effects with 9/11?

It's the only other time in American history that foreigners have attacked the American capital. So in that sense it has similarities. But of course this wasn't a terrorist attack. This was an attack by a country at war with America, as Britain was at that time. But it was one of the most humiliating military defeats of American history—to see their capital burned, their Army literally running away, and President Madison and his wife, Dolley, forced to abandon the White House. It was a catastrophe.

Britain and al Qaeda are also the only two outside powers to cause an American president to be a fugitive in his own country. President Madison ended up hiding in a shack in Virginia. President George W. Bush took refuge at an Air Force base in Nebraska.

Thankfully this is the only occasion one can compare good old Great Britain and al Qaeda!

What made you want to write this book?

I had previously written a book called To War With Wellington, about the Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon's army in the Peninsula War, in Spain and Portugal, and then went on to win the Battle of Waterloo, in 1815. But in the spring of 1814, after Napoleon abdicated, the British suddenly realized they had not a French enemy but an American one.

The Americans had declared war on us in 1812 because we were interfering with their trade with France. So in 1814 the Brits decided to deal with America. And I discovered that a great number of the soldiers, whom I'd covered in detail in the Peninsula campaign with Wellington, were diverted to America. They marched on Washington, routed the American forces, and found the White House empty, with the president's dinner still on the table. It was too good a story to miss!

Was it difficult for you, as what the Americans used to call a "Britisher," to remain unbiased?

Working as a BBC journalist for many years, I learned to be unbiased. And I wanted to tell the story so that people on either side of the Atlantic can understand the facts rather than the spin. That's why I tried to use as many American accounts as British ones. And there were some wonderful American eyewitnesses present.

In Britain, you're a household name. For those outside the U.K., can you tell us about the Swingometer?

I worked in television for nearly 50 years. One of my jobs was covering elections. And I occasionally found myself struggling to present them in an interesting way. So I used something called the Swingometer, which was invented by a very fine Canadian political expert, Robert Mackenzie, back in the '50s.

Basically, we had this huge pendulum that descended from the studio ceiling with wonderful bright lights on it. And as the votes changed, it swung from side to side. So, if the Tories were winning, the pendulum would change from red to blue. It was a great way to show how the election was going.

Most people assume that hostilities between the U.S. and Britain ended with the War of Independence. But as the book shows, the 1812-14 conflict can be seen as a settling of old scores from that war.

It was the filling in of unresolved problems, like the Native American problem. One of the most disgraceful things the Brits did at the Peace of Ghent, after the war, was to neglect Indian rights.

The Indians had been loyal allies to Britain in the war with America in 1812. But they abandoned them completely in order to get peace. As a result, the Americans were able to go into Ohio and Illinois and Michigan and other areas that had belonged to Native Americans without any scruples.

You say that the 1812 war showed the strength and weaknesses of both nations. How so?

Well, it showed the enormous strength of the British Navy and the enormous weakness of the American defense system. It really was a remarkable paradox that America, which had won the War of Independence, then abandoned the need for a regular army to defend the newly independent nation.

And so you had this extraordinary situation where the president was unable to put a serious force together to defend the country. So they were no match for the battle-hardened veterans the British brought over.

The weakness of the British was their arrogance in continuing and trying to win Louisiana. Andrew Jackson completely destroyed the British Army, at the Battle of New Orleans.

The American strength was that it was full of enthusiastic young people willing to die to defend this wonderful new country. On the night of the 24th of August it must have looked to the Americans as if they were doomed. They weren't, of course, because there were seven million of them facing only 4,500 British troops.

You reconstruct the events of August 1814 in almost hour-by-hour detail. Can you shed some light on your research and writing process?

I did 18 months of research altogether. I made two trips to Washington. I went to the White House and saw the burn marks on the walls. I also retraced the steps of the British Army going up the Potomac River, all the way up to Upper Marlboro [Maryland], then across to Bladensburg.

The battlefield at Bladensburg is quite evocative still. You can imagine the American cannons opening up on the British as they crossed the bridge. It must have been a devastating moment for the British. They lost a lot of men in the first moments of the battle. But the British were extremely battle-hardened. One guy would fall down and die, and his mates would just close the gap and keep marching. I think the Americans, seeing these redcoats keep marching into their cannon fire, couldn't cope with that.

The book has many fascinating characters. Tell us about Dolley Madison, the president's wife.

She was an extraordinary contrast to her husband. President Madison was very cerebral, not a hugely outgoing person. She was everything he wasn't—outgoing, a tremendous host, a real First Lady. She used to wear a turban and exotic dress and go around at parties offering pinches of snuff and ice cream to the guests.

It was a completely novel kind of White House. Very wisely, she invited people of all political parties. And fortunately for them, and for all of us, the war ended after only four months, with the American victory at Baltimore. And so I think, ultimately, Madison and his wife have gone down as a successful president and first lady, despite the humiliation of Washington.

One of the happy outcomes of the war, for the American side, was "The Star Spangled Banner," wasn't it?

[Laughs] Yes. Francis Scott Key was so inspired at seeing an American flag still flying over Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, after 24 hours of bombardment that he pulled a bit of paper out of his pocket and wrote down the poem that would become the American national anthem. When I tell a British audience that we Brits inspired the American national anthem, they all roar with laughter, and clap! [Laughs heartily]

What was the legacy of the conflict?

The War of 1812 is not a particularly prominent part of the history of Britain. It was massively overshadowed by the Napoleonic war and by Waterloo that followed—the war in America is just a sideshow.

But it wasn't for Canadians or the Americans. It was madness on Madison's part to declare war on the country with the biggest navy in the world. But having faced up to the Brits, the Americans realized that the way forward was not to look east across the Atlantic to Europe—but west, particularly after the British abandoned the Indians and failed to take New Orleans. And this tremendous surge of people moving into the Midwest was key in creating the huge, exciting, and powerful country that America became.

Today, the war of 1812-14 is mostly the subject of jokes between prime ministers and presidents. When David Cameron visited the White House in 2012, President Obama joked that his countrymen had once "really lit the place up." Bob Dylan even penned a couplet about the burning of the White House for his song "Narrow Way."

So hopefully I won't need my flak jacket when I come to America for the book tour! Actually, I think Americans will enjoy this story as much as the Brits. It's a fascinating commentary on the long, shared history between our two countries.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.