Despite ISIS Threat, Looted Antiquities Returning to Iraq

Does return of ancient objects to Baghdad send a “strong message” in face of ISIS threats, or put the artifacts in danger of destruction?

At a recent ceremony in Washington, D.C., to repatriate more than 60 ancient artifacts smuggled out of Iraq and into the U.S., the Iraqi ambassador was firm that he had “no concern” regarding the safety of the objects once they are returned to his country, which is grappling with ongoing Islamist attacks on its museums and archaeological sites.

Ambassador Lukman Faily characterized the cooperation between the two countries to track, seize, and return smuggled artifacts as a “dry-well approach” to ensure that the illegal sale of antiquities won’t serve as a “fund-raising source” for terrorist groups like the Islamic State (also known as ISIS).

Returning the artifacts, he said, will “send a strong message to [ISIS] and its destruction that we are committed to defeating the terror, rebuilding our country, and preserving its cultural heritage.”

ISIS has been implicated in the destruction of cultural sites in western and northern Iraq since 2014. Its campaign appears to have escalated over the past months, however, with the release of a video showing militants destroying objects in the Mosul Museum and reports of attacks on the Assyrian cities of Nineveh, Nimrud, and Khorsabad. (Learn more about ISIS attacks on historical sites.)

While the extent of the damage has yet to be verified, the Islamist social media campaign has captured the attention of a global audience, raising questions about the wisdom of returning objects to a country whose cultural heritage is under assault.

But archaeologists working in areas outside of ISIS’s control agree that returning the artifacts to the National Museum is the right move. The artifacts will be stored in vaults at the National Museum in Baghdad, and the heavily fortified Iraqi capital is considered able to resist an invasion by ISIS.

Robert Killick, co-director of the Ur Region Archaeology Project, says that as the repatriation ceremony was taking place, his team was depositing more than 200 artifacts from their current excavations at Tell Khaiber in southern Iraq at the National Museum in Baghdad. “We have no concerns about handing over these antiquities or, indeed, of continuing our work in Iraq,” he says.

Destination: National Museum, Baghdad

The National Museum in Baghdad, which was looted following the 2003 invasion, reopened less than a month ago. Approximately one-third of the museum’s 15,000 artifacts that went missing in 2003 have been returned. It’s not believed that any of the artifacts repatriated last week were part of the museum’s collection.

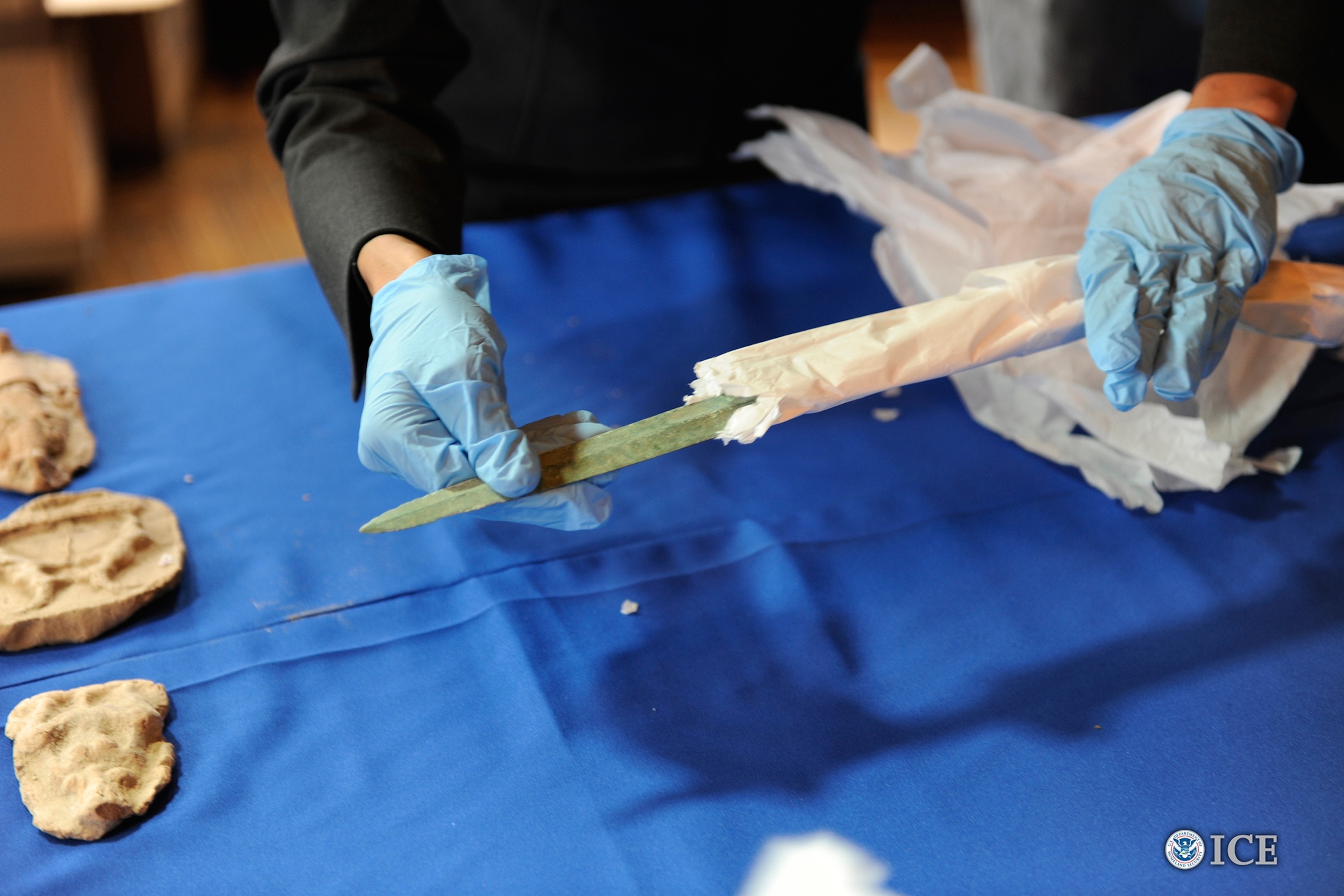

Among the objects being returned is a 2,700-year-old head from a stone sculpture of a composite creature known as a lamassu. Officials from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) identified the lamassu as being from the palace of Sargon II, an Assyrian king, near Khorsabad, one of several sites confirmed by Iraqi officials to be significantly damaged by ISIS.

All of the artifacts going to Baghdad were seized during ICE investigations beginning in 2008 that predate the rise of ISIS in Iraq. Many may have been looted during the chaos that followed the U.S. invasion of the country in 2003.

Margarete Van Ess, head of the German Archaeological Institute's Iraq field office, concedes that repatriation of objects in times of conflict can be “disputable,” but that “always waiting for better times will not solve problems, and the repatriation of stolen objects is an important gesture to Iraq.”

“The best response to the current situation in northern Iraq is for archaeologists to expand their efforts in other parts of the country,” Killick said. “[ISIS] may be able to destroy monuments and artifacts, but they cannot erase our knowledge of Iraq’s past, and that is what we and our Iraqi colleagues are adding to all of the time.”

Bad Timing, or Vote of Confidence?

The timing of the repatriation, in light of the recent reports of ISIS-led destruction of archaeological sites, may be seen as an “unfortunate coincidence,” according to one expert on the matter. However, U.S. and Iraqi officials present at the ceremony stressed that there was no connection between the return of the artifacts and the recent cultural attacks in Iraq by ISIS, and that the lengthy process of repatriation was put in motion years ago.

Repatriations “are not done spur of the moment,” agrees Patty Gerstenblith, director of the Center for Art, Museum, and Cultural Heritage Law at DePaul University, in Chicago, and chair of the U.S. State Department’s Cultural Property Advisory Committee.

“I think these artifacts will be quite safe,” says Gerstenblith. “Baghdad is not under threat … [and] I think it illustrates a vote of confidence by the U.S. government in the ability of the Iraqi government to keep these objects safe. It is also the appropriate thing to do under existing laws.”

While media attention has been focused on the safety of museums and archaeological sites in the Middle East, University of Chicago professor McGuire Gibson, an expert in ancient Iraq and member of the National Geographic Society’s delegation to cultural sites following the 2003 U.S. invasion, offers a more sobering observation.

“Since it seems to have been decided not to let Baghdad fall to [ISIS], it should be relatively safe to have the objects return now … But can we predict that museums in Europe and the U.S. will not also be attacked at some time in the future? Look at the recent [attack on the Bardo Museum] in Tunisia. What is next?”

Follow Kristin Romey on Twitter.