How Jackie Kennedy helped save an iconic ancient Egyptian temple

Sixty-five years ago, the monumental Abu Simbel was destined to disappear beneath the floodwaters of a new Nile dam. Then the first lady of the United States stepped in.

To secure its future, Egypt had made the hard decision to let go of its past. It was 1960, and construction had just begun on southern Egypt’s Aswan High Dam, which would generate hydroelectric power, provide more arable land, and control the flood-prone Nile River. But for all the good a dam would do, it was also going to be disastrous for the area’s archaeological wonders. The massive reservoir was expected to destroy dozens of priceless historic sites, including the majestic twin temples of Abu Simbel.

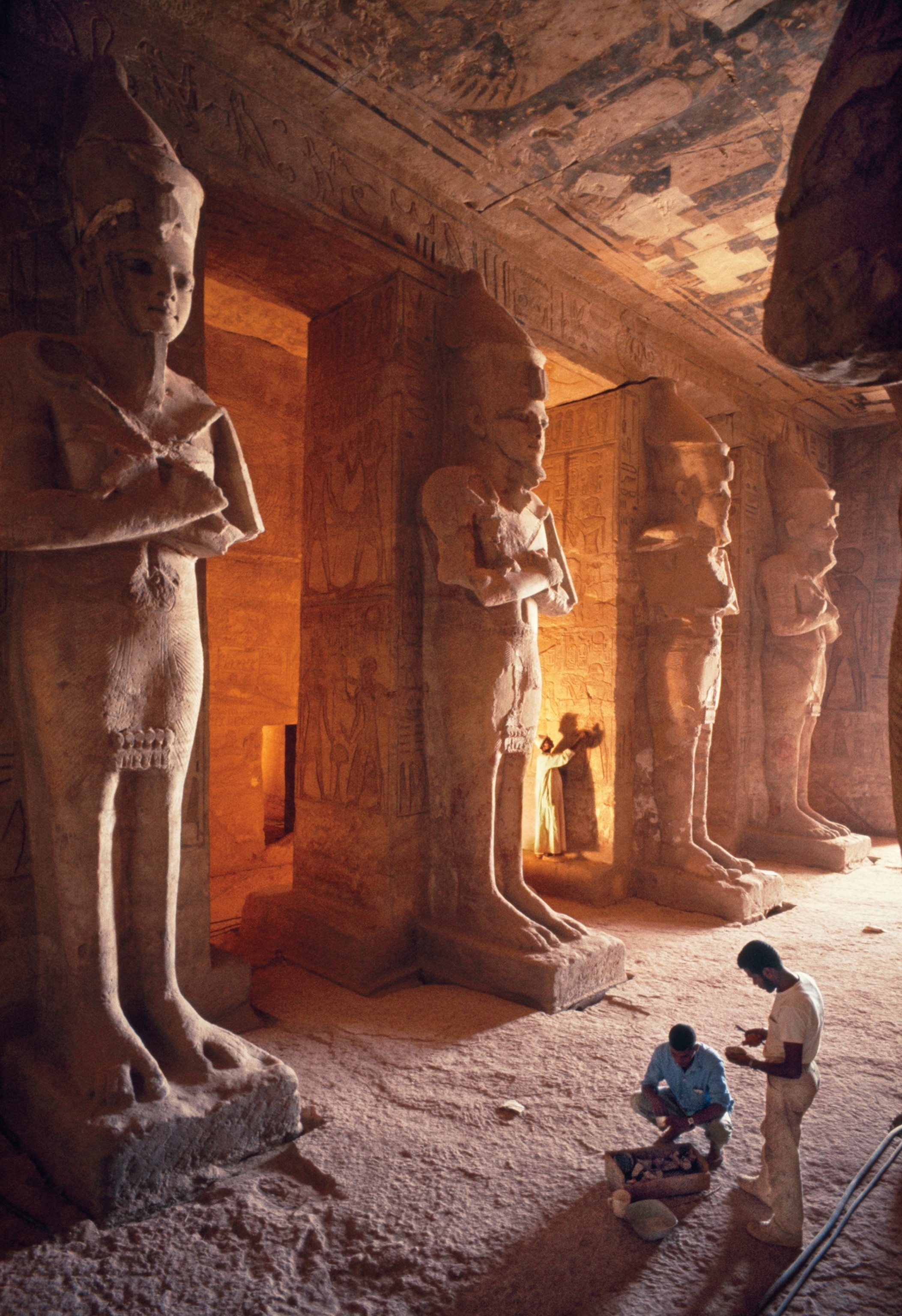

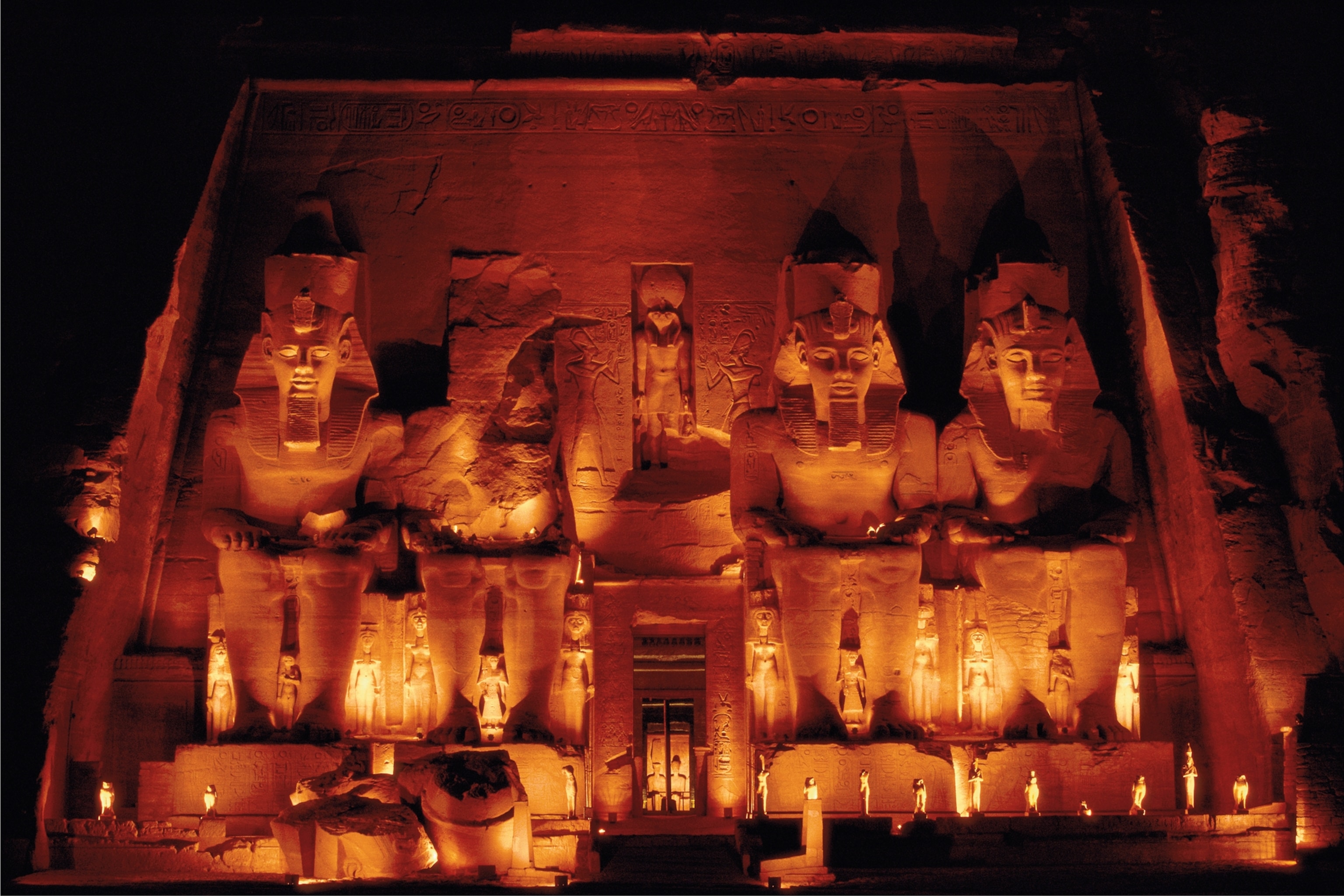

Built more than three millennia ago, the monument was commissioned by Ramses II and chiseled directly into a sandstone cliff on the western bank of the river. The imposing facade of the main temple was guarded by four towering Ramses II colossi, each 67 feet high, and the nearby smaller temple was dedicated to Queen Nefertari and Hathor, the goddess of love, music, and dance. The temples’ inner sanctums were carved deep into the cliff and filled with statues of Egyptian gods and reliefs depicting victorious military battles. It was one of Egypt’s finest pharaonic treasures, and it was about to be lost forever.

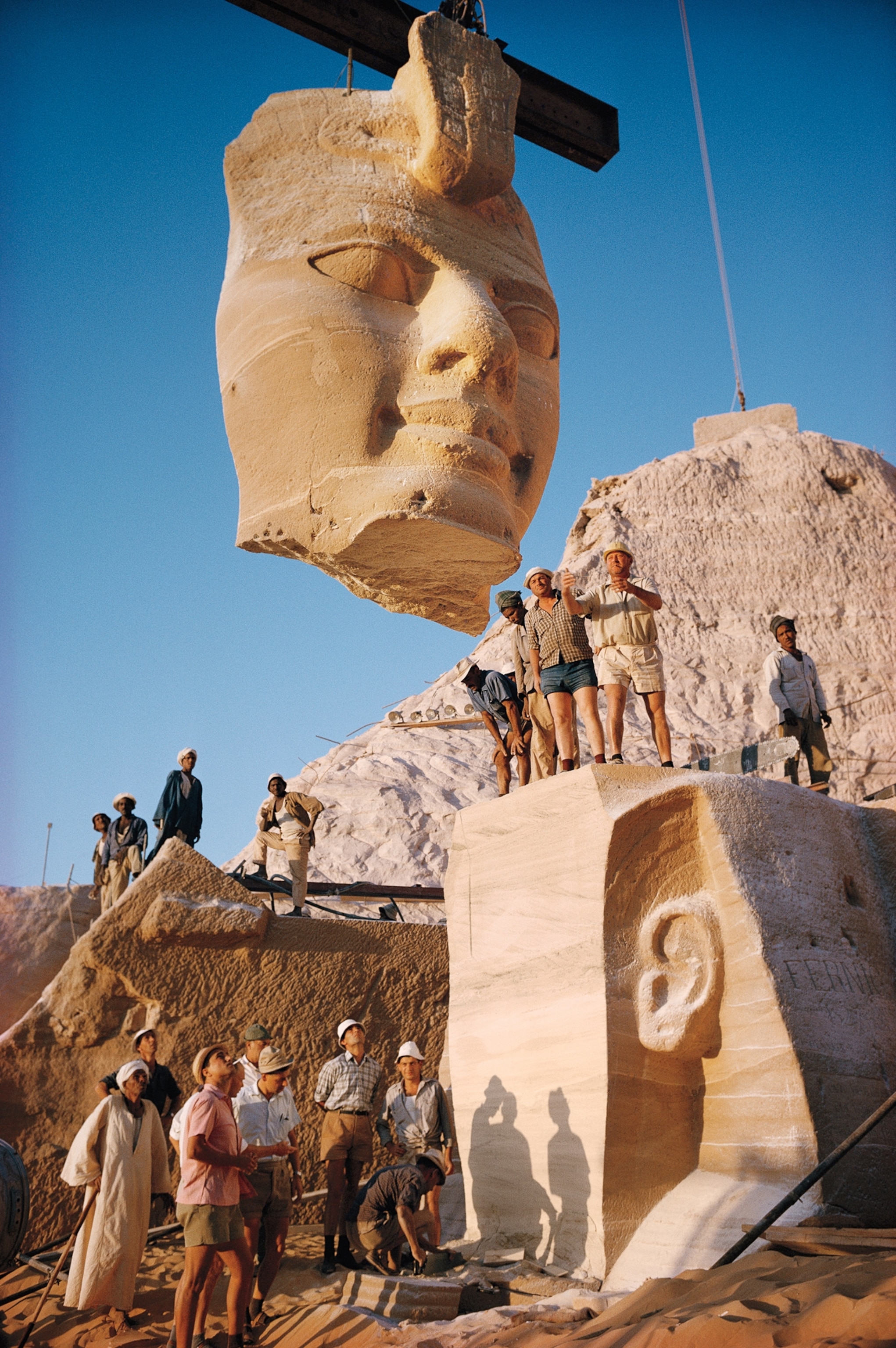

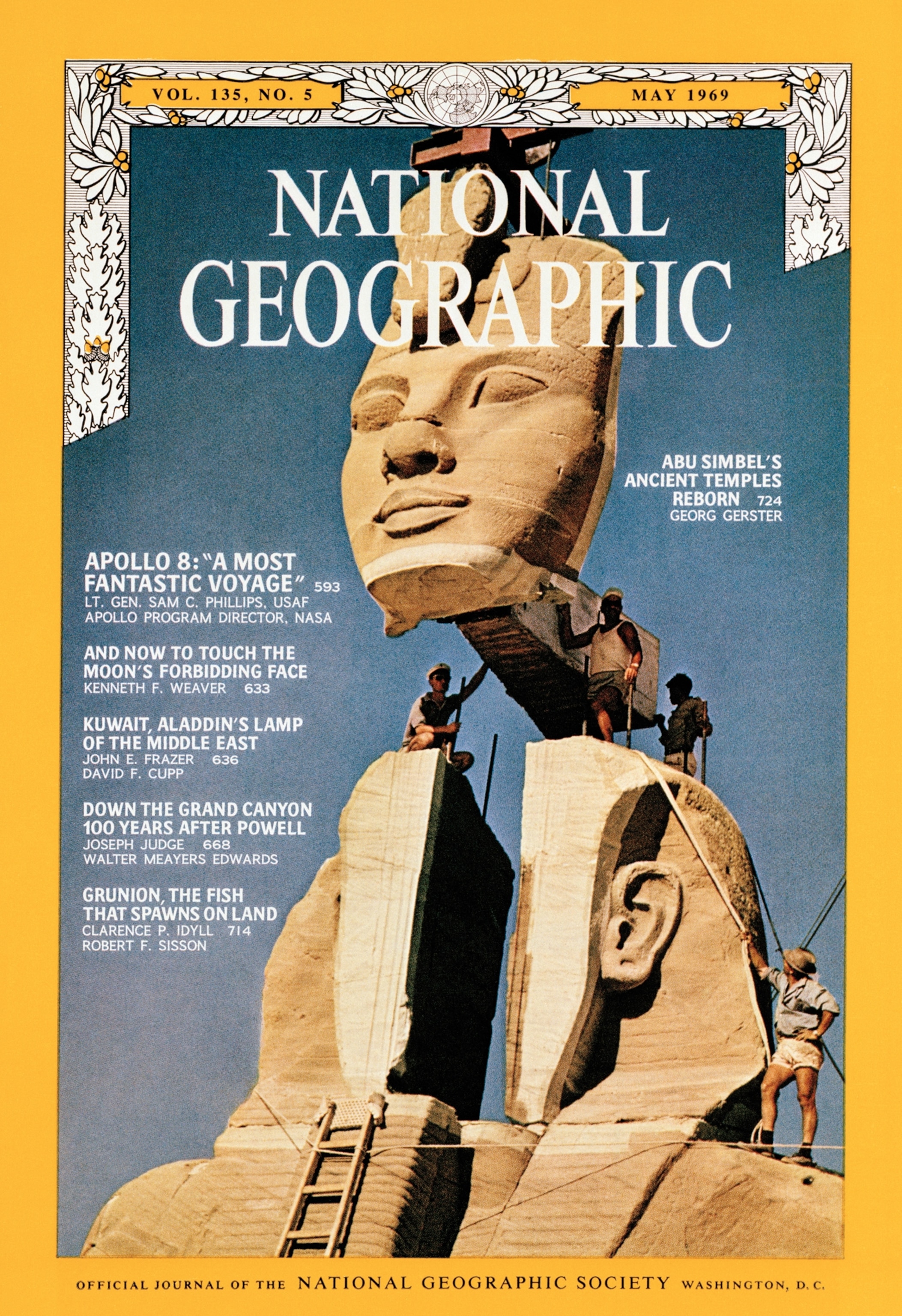

To save Abu Simbel, an international consortium of conservationists launched an unprecedented rescue mission before the dam’s completion in 1970. The plan was to cut the entire complex out of the mountain by meticulously deconstructing each stately chin, cheek, and crown—more than a thousand pieces in total—and then transporting and reassembling them on higher ground. In order to succeed, it would require unheard-of orchestration between the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and thousands of archaeologists, architects, and Egyptologists from dozens of countries. But with a cost equivalent to $400 million today, the entire undertaking seemed far too expensive to pull off—until an unlikely diplomat intervened with a bold vision to support a project that ultimately transformed UNESCO and reshaped how future leaders in her role would go on to effect change.

(Meet the woman who helped save Egypt's temples from certain doom.)

Half a world away, future First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy had been closely monitoring the fate of Abu Simbel. Ever since reading about Howard Carter’s 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, she’d remained fascinated by the mummies and pyramids of ancient Egypt. Years later, when a friend gave her a copy of the UNESCO Courier, the official magazine published by UNESCO, which called on world leaders to save Abu Simbel before it was too late, she vowed to protect the memory of the once mighty empire she’d learned about as a little girl.

After John F. Kennedy became president in 1961, Jacqueline got to work convincing her husband why it would be advantageous for the United States to get involved. But rather than just talking behind closed doors, the new first lady decided to go through more official channels. She crafted a carefully composed memo likening the loss of Abu Simbel to “letting the Parthenon be flooded,” underscoring the research possibilities of the temples and how important they were to the whole of Africa, a region with which JFK was trying to strengthen diplomatic ties during the Cold War.

(Epic engineering rescued colossal ancient Egyptian temples from floodwaters.)

She gave the note to White House adviser Richard Goodwin, who then helped draw the president’s attention, and the financial might of the U.S., to Egypt. “I convinced the president to ask Congress to give money to save the tombs at Abu Simbel,” Jacqueline proudly recalled later. But there was a caveat. “He [only would] if I could convince [Congressman] John Rooney of the Appropriations Committee, who was always against giving money to foreigners.” She was ultimately successful, and the U.S. government announced its intention to cover up to one-third of the cost. The rest would be financed by Egypt and UNESCO.

Of course, she wasn’t the first woman in the White House to use soft diplomacy as a conduit for influencing matters beyond traditional lines of negotiation. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who famously visited troops in the South Pacific during World War II, was often referred to as the “eyes, ears, and legs” of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. But prior to Jacqueline, a first lady’s diplomatic duties almost always took the form of trips abroad or hosting dignitaries at the White House. “A woman’s credibility was part of what created liking and friendliness and cooperation, and would soothe the relationship often between the heads of state,” says Elizabeth J. Natalle, author of Jacqueline Kennedy and the Architecture of First Lady Diplomacy. “[She] created the blueprint for the way in which first ladies use different kinds of communication tools.” Pointing to initiatives like First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let Girls Learn, a plan to increase educational opportunities for young women worldwide, Natalle adds that now “first ladies can actually influence policy.”

A plan was put into place in 1963, and a team of Egyptian, German, French, Swiss, and Italian workers—among them master marble carvers from Carrara, Italy—then cut Abu Simbel into enormous blocks weighing up to 33 tons using a variety of tools, including handsaws. The blocks were numbered and taken via flatbed trailers to a new artificial sandstone mountain 200 feet higher than the old Nile shoreline and 690 feet inland. Crane operators resurrected the grand pharaonic work piece by piece, like a giant Lego set successfully put back together again.

Thanks in part to Jacqueline Kennedy’s powerful private lobbying, Ramses II and the rest of the Abu Simbel statues reign safely again in southern Egypt, ready to survive another 3,000 years. In honor of the support fostered by the first lady, Egypt offered the U.S. the smaller temple of Dendur, a first-century B.C. shrine also saved from the Aswan High Dam, which is now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Ultimately, JFK never got to see the end result of his wife’s work. He was assassinated before the relocation of Abu Simbel even began.

Today Jacqueline’s preservation efforts in the U.S.—from the White House to New York’s Grand Central terminal—are widely lauded, but her contributions in Egypt have been largely overlooked. However, her daughter, Caroline, once remarked that her mother “felt that of equal importance to her White House restoration were her far less well known efforts as first lady to save Abu Simbel.”

While there was little public recognition of the role she played, Jacqueline was instrumental in securing funding for a venture that helped set the stage for future conservation endeavors across the globe. The work done to save Abu Simbel was a catalyst for UNESCO’s World Heritage initiative that now safeguards thousands of notable landmarks, from the ancient ruins of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat to the water channels of Venice. “That campaign was very symbolic in many ways,” says May Shaer, UNESCO’s chief of the Arab States Unit for World Heritage. “It established a common standard to identify and protect cultural and natural properties that are considered to be of significance for all humanity.”

Kate Storey is the New York Times bestselling author of "White House by the Sea" and the Features Director at Rolling Stone. She was previously a staff writer at Esquire, where she covered culture and politics, and has written long-form profiles and narrative features for Vanity Fair, Marie Claire, Town & Country, and other publications.