Decades ago, this pollution disaster exposed the perils of dirty air

A survivor of the five-day smog crisis in Pennsylvania recalls: "We all knew the air was bad. We didn't realize it was going to kill people."

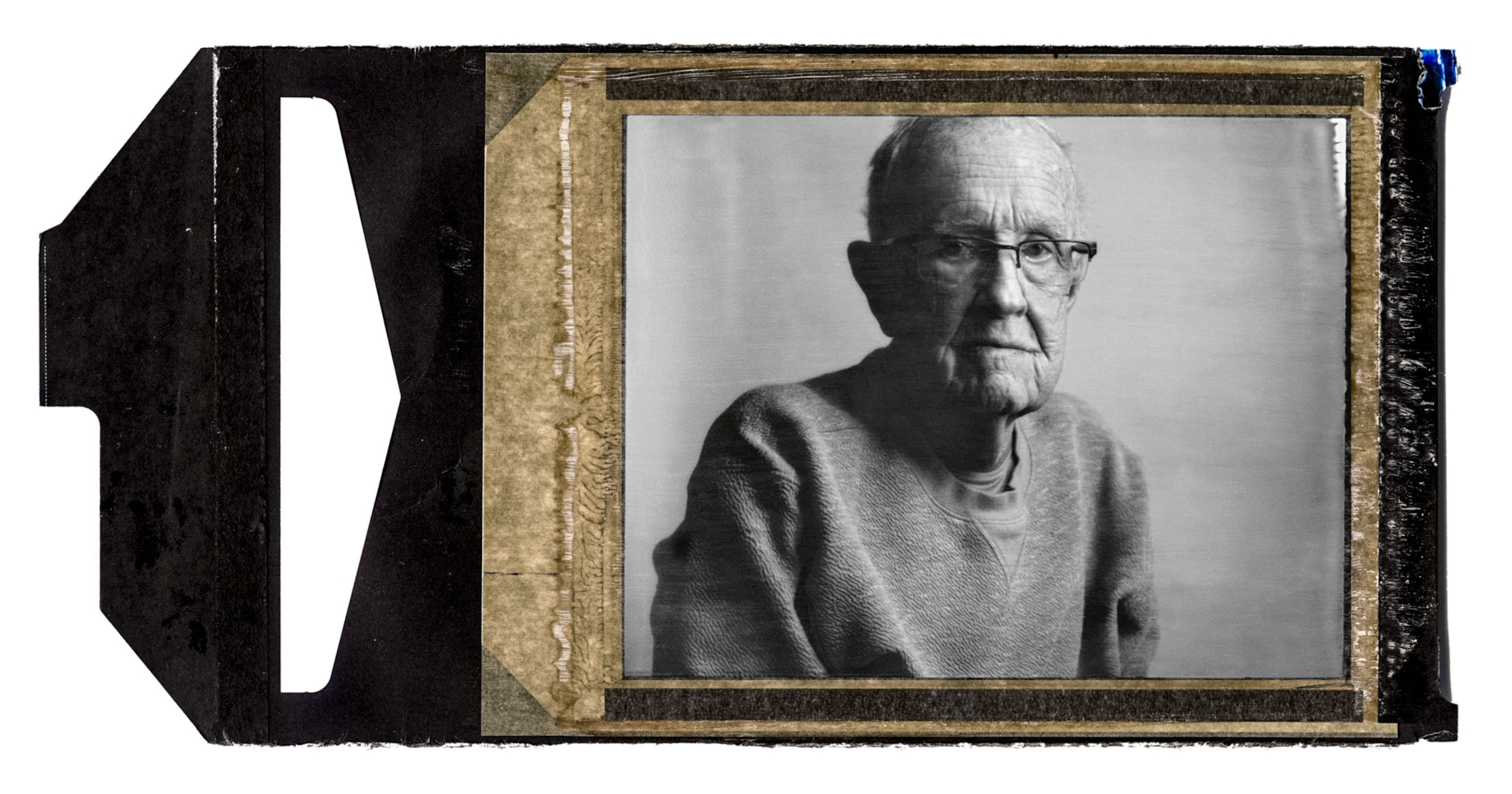

Strangers still find Charles Stacey, who is 88 and lives in the Pennsylvania town of Donora, to ask him about those five October days. Sometimes they use words that appeared in the headlines: the Incident, the Disaster, the Death Smog. The broadcaster Walter Winchell had one of the most famous voices in America back then, and that’s what Stacey remembers most vividly—walking into his family’s house the evening of October 29, 1948, and turning on the radio.

“And Walter Winchell was saying, ‘There’s a little town in western Pennsylvania where people are dropping dead,’ ” Stacey recalls. “And I said to myself: ‘I wonder where that could be?’ I could barely see people right across the street, and we don’t have any wide avenues here in Donora. We all knew the air was bad. But we thought that was a way of life. We didn’t realize it was going to kill people.”

He’s cordial, replying to one more stranger on the phone; Stacey is retired, after a career as a teacher and school superintendent, and he understands that every so often what happened in Donora needs retelling. Today’s query is from the West Coast, where since August an extraordinarily fierce wildfire season has made the air so bad, on and off, that a few of the region’s cities have registered the highest atmospheric pollution levels in the world. One Wednesday in September the sky over the San Francisco Bay Area stayed deep orange, the palette of a smoky sunrise, all day long.

Frantic texts and social media spread visuals of that day faster than headlines could. Chances are you saw one of those images, no matter where you live: the city skyline or the Golden Gate Bridge, dusky at midday, shrouded in eerie color. A British television reporter interviewed people walking uneasily in the orange outdoors. A woman said, “It feels like doomsday.” A man said, “It feels like the end of the world.” (Air pollution made COVID-19 worse. Will cleaner air from lockdowns inspire us to do better?)

In fact, as those of us in Northern California learned from weather experts, there is a benign half to the explanation of what took place here that day in September—and in Donora, 72 years ago; and in London, in 1952, during a catastrophic event dramatized recently in an episode of the television series The Crown. Sometimes, for ordinary weather reasons, the atmospheric layers closest to us (normally warmer below, colder above) get flipped. A warm layer hovers up high for a while, preventing cooler air beneath from rising and dissipating. You hear this described in weather reports as a “temperature inversion.” In principle, there’s nothing worrisome about an inversion. It just makes for temporarily trapped air, held in place down where the people are.

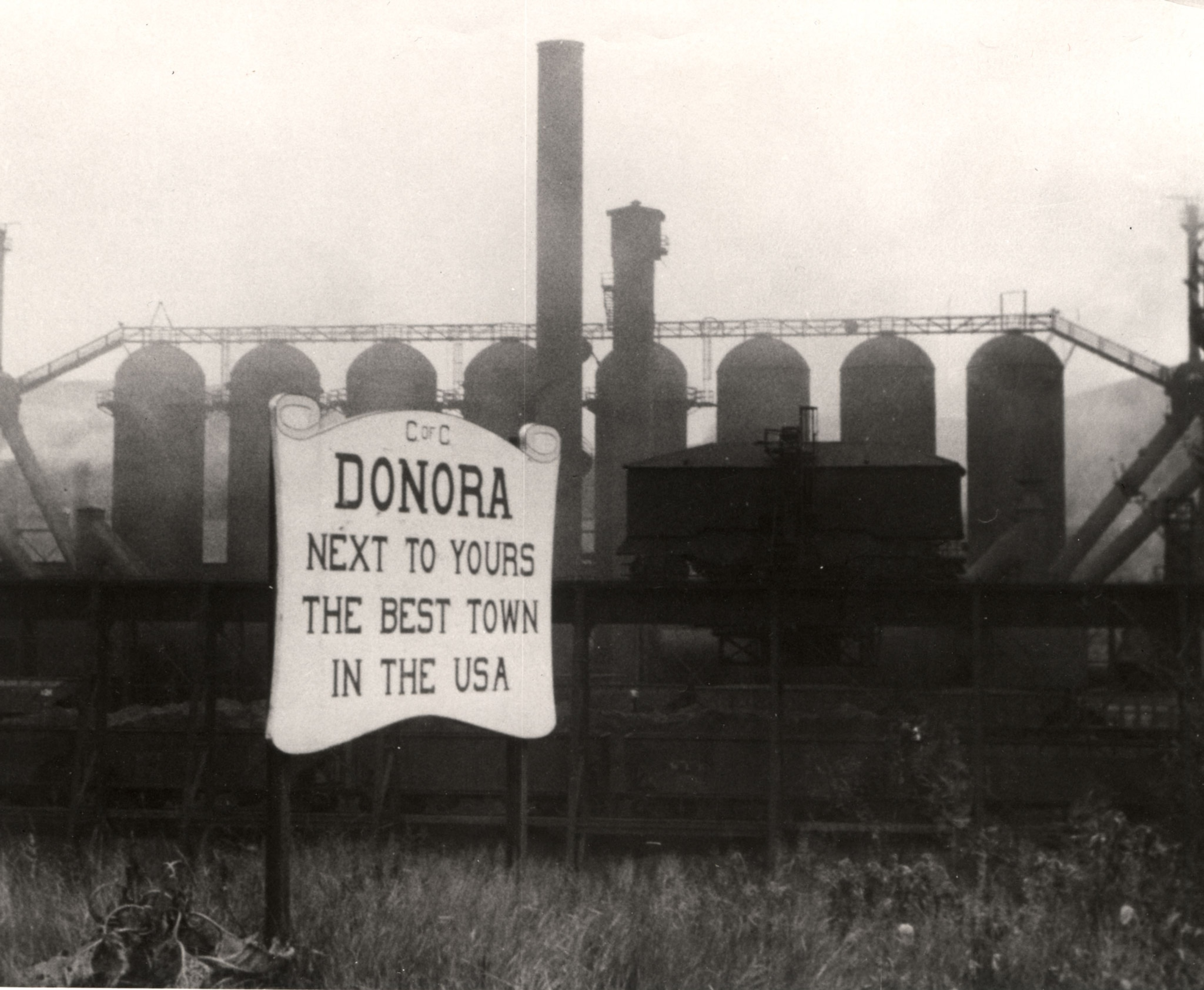

But when the layers invert amid an ongoing foul-air situation, the result can be terrifying. In Donora, an industrial center where massive zinc and steel wire mills had for decades poured contaminants into the air, an unusually stubborn inversion settled in on the morning of October 27, 1948, over the Monongahela River’s horseshoe bend alongside town. The inversion trapped Donora’s air, its emission toxins mixing with river fog and thickening with each passing day. The first person the bad air killed died at 2:00 in the morning four days after the inversion began.

From an aftermath report: “More followed in quick succession … by nightfall word of these deaths was racing through the town … the physicians’ telephone exchange was flooded with calls for medical aid … It was reported that streamers of carbon appeared to hang motionless in the air, and that visibility was so poor that even natives of the area became lost … By 11:30 that night, 17 persons were dead.”

That report, published in 1949 by the U.S. Public Health Service after months of investigation in Donora, was one of history’s first close examinations of air pollution as a peril to human health. The “thick killer fog,” as Winchell called it, lasted less than a week, but it would set Donora into modern textbooks and science courses—not because anything abnormal had spewed out of the mills, but because a persistent temperature inversion forced attention to a contamination hazard of global proportions.

The inversion wasn’t the problem. The inversion was a magnifying glass. A crucial new field of study must now be fully recognized, U.S. Surgeon General Leonard Scheele declared in his preface to the report: At least 20 Donora citizens had died during or immediately after the crisis, and thousands more were sickened. Humanity’s well-being depended on learning why—and on understanding what everyday industrial discharge was doing to other places that hadn’t made national news.

“It was not until the tragic impact of Donora,” Scheele wrote, “that the Nation as a whole became aware that there might be a serious danger to health from air contaminants.”

Of course people had long known smoky air was irritating, Scheele wrote. The word “smog” had been in use since the turn of the century; it appears to have been invented by someone in Britain describing the murky mix of fog and coal smoke that sometimes darkened London. And inversions atop industrial fumes had killed before: In 1930, when one much like Donora’s covered a Belgian river valley full of metal plants and factories, more than 60 people died during three days of increasingly polluted stagnant air. There’s a memorial to those victims in the town of Engís: a statue of a distraught kneeling woman, her hands pressed to her cheeks.

In Donora, current population 6,500, the memorial is the town museum. It fills one floor of a glass-fronted former bank building, and the walls and cabinets inside hold some mill artifacts and baseball memorabilia—the great St. Louis Cardinals player Stan Musial was from Donora. But the whole collection is named, as its storefront sign proclaims, after its biggest and most prominent display. THE DONORA SMOG MUSEUM, the sign reads. CLEAN AIR STARTED HERE.

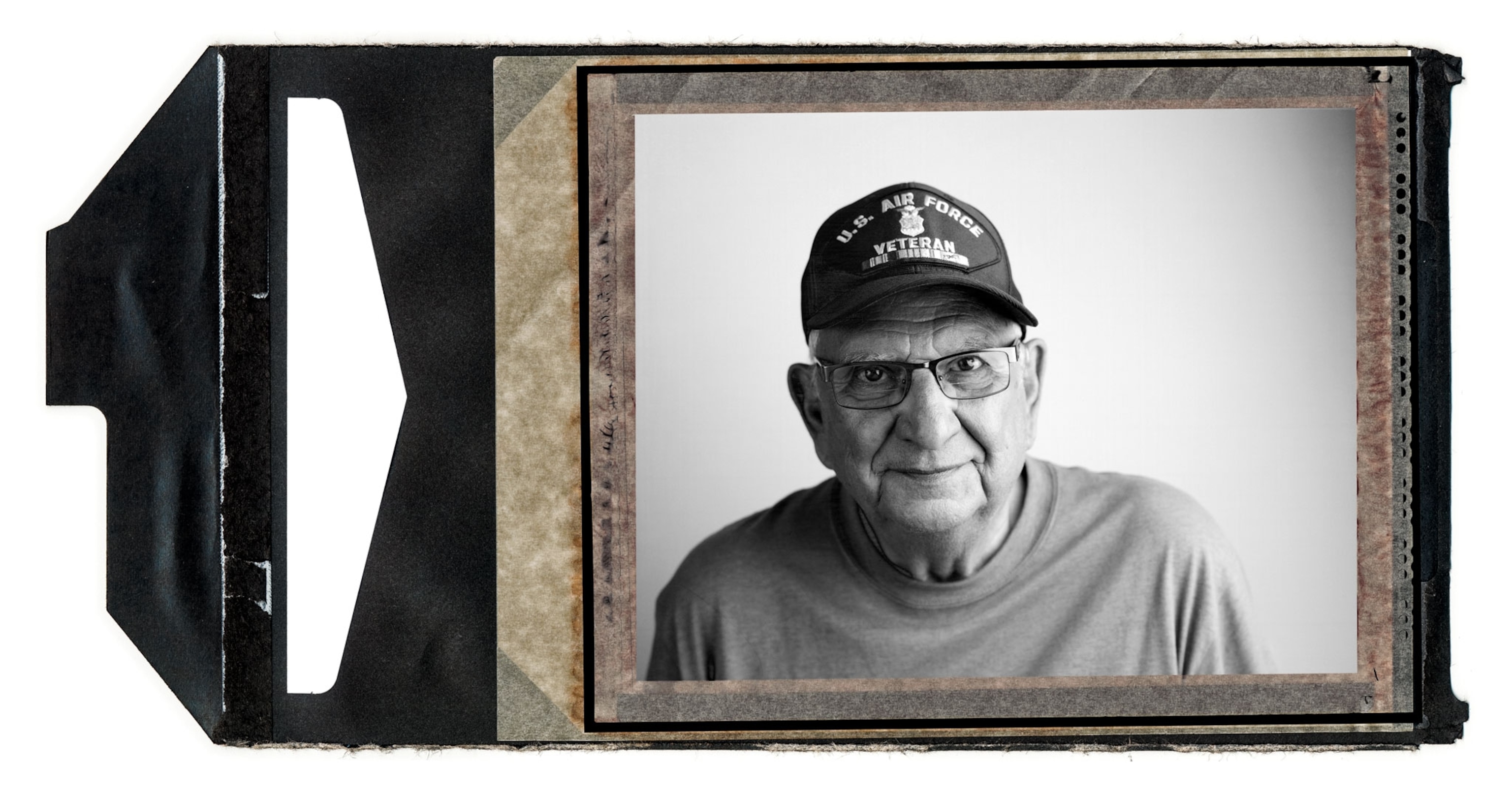

As to the bottom line on the sign—call it aspirational. “There should be an asterisk beside that,” says Brian Charlton, the Donora history teacher who has served as curator since the museum opened in 2008. “The attempt to clean air started here. But this was really the event that started people nationally wondering what industry is putting into the environment, into the soil, the water, the air. Nobody had ever actually questioned that before.”

Among the museum’s memorabilia are small guideposts to the seven contentious decades that have followed the Donora Smog: advances, retreats, and ongoing battles over the role and obligations of humans in environmental damage. “Death Smog ‘Act of God,’ Says Steel Company”—that’s a framed article about the protracted effort by American Steel and Wire, the owner of the mills and a subsidiary of the powerhouse U.S. Steel, to discourage emissions research and blame strange weather for the deaths and sickness.

And it wasn’t solely industry representatives who preferred the disaster be forgotten as swiftly as possible. Some families did sue, eventually winning a financial settlement that barely covered their legal costs. But 13,000 people lived in Donora during the 1940s, nearly all connected directly or indirectly to the vast complex of mills, and Charles Stacey says he has contemporaries who still complain that too much fuss was made over that one bad October week. “Every year, in the spring and fall, we had these smoggy, smoggy days,” he says. “And we were still here.”

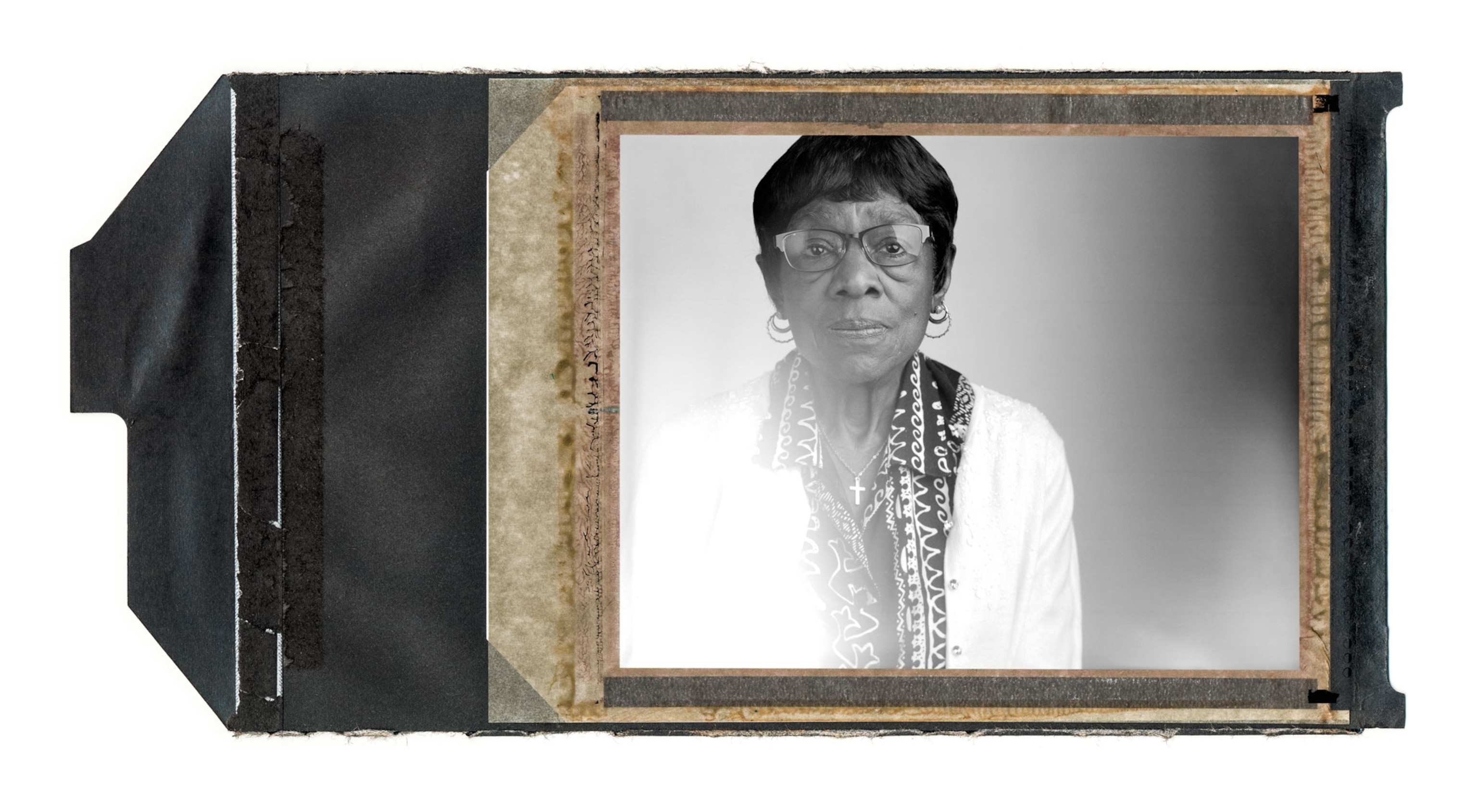

Charlton and epidemiologist Devra Davis, a Donora native, say local people of their parents’ generation maintained a kind of civic omertà about October 1948. “There were two stories never discussed in our Jewish family—one was the pollution and the other was the Holocaust,” says Davis, who was two during the smog crisis. As an adult she dug into its history, sometimes prying details from the reluctant, for her 2002 book When Smoke Ran Like Water: Tales of Environmental Deception and the Battle Against Pollution. “People just didn’t want to talk about it,” she says. “Of course they didn’t want to talk about it. It kept most of the town employed.” (See where air pollution is lethal around the world.)

Charlton, whose wife was born in Donora—he’s from five miles upriver and likes to joke that his marriage is the only reason he’s accepted as a semi-native—says it’s important not to mis-imagine the silence as ignorance. Inside the zinc plant, which for a time was the largest in the world, workers knew three hours near the furnaces could bring on “zinc shakes”: coughing and nausea from inhaling metal fumes. They drank a concoction regarded as medicinal (milk, ice, oatmeal, whiskey) and returned to work the next day. “They weren’t dumb,” Charlton says. “They were making good livings. They were able to save money. So they were going to close one eye to the fact that, yeah, this is probably destroying our health.”

This is the same conscious calculus that’s been made over and over, before and since, by individuals and societies a long way from the Pennsylvania steel belt. Charlton is 62, not yet born in October 1948, but he says it’s clear to him that every adult in town knew how bad that week really was.

“It was reported almost immediately on NBC News, and the reason was that people from Donora were calling out to find out what was going on—and people outside were calling into Donora,” he says. “Nobody could actually get into Donora. There was literally … like a wall you went into, where you just could not see anymore. That’s how it’s been described to me.”

On one shelf at the museum is a portable oxygen tank, one of two that volunteer firefighters carried house to house as pleas for help multiplied. “Bill and Jim,” Charlton says. “Jim worked in the mill. Bill was a postal carrier. They’d talk about how heartrending it was. They’re coordinating through walkie-talkies, they go to a house, the victim’s on the floor gasping for breath, they give oxygen until the victim starts breathing again—and then they have to move on to the next house, even though the victim’s family is pleading with them to stay.”

In 1955, seven years after Charles Stacey heard that Walter Winchell broadcast, the U.S. Congress approved the first federal legislation to contain the word “pollution” in its title. By the time the Air Pollution Control Act was signed into law by President Dwight Eisenhower, the little western Pennsylvania town’s killer fog had been pushed from the news; in December 1952, over five days, a far more devasting inversion paralyzed London. If you happened to watch episode four in the first season of The Crown, you saw the deadly chaos of what history now calls London’s Great Smog: Airports closed, birds flew into buildings, emergency rooms backed up, men with flashlights walked alongside creeping double-deckers to help the drivers find their way.

The smog details are true to history: London’s industry and home heating furnaces used coal prolifically, and during the post-World War II years Britain’s higher quality coal was reserved for export. The coal burned domestically was of the cheapest, dirtiest variety. There was nothing unusual about the city’s river fog mixing with smoke (remember, this is where the word “smog” came from), but the 1952 inversion held down dangerously thick levels of airborne pollution for five days straight. In one scene of the Crown episode, a woman exits a frenzied emergency room, steps out into the viscous fuzz of daytime, and is smashed by an oncoming bus. And early in the hour, a horrified civil servant shows a colleague a just-off-the-wires weather dispatch that hints at what’s about to occur. As the colleague skims the dispatch, looking bewildered, the civil servant asks (slowly, drawing out his words to ominous effect): “Does the name Donora mean anything to you?”

The London Smog’s final death toll, encompassing people who died in subsequent months at far higher rates than usual, was put at about 4,000—until a more recent scholarly re-examination of health data tripled the estimate to 12,000. That’s now the more widely accepted total, and one of the researchers who helped reach that conclusion was Devra Davis. She now lives in Wyoming, after a career at multiple university and government advisory posts. She’s convinced she still carries the personal legacy of a childhood breathing Donora’s mill-fouled air.

“I have asthma,” Davis says. “I don’t have it very often. But there’s no question in my mind that my asthma is related in large part to where I grew up. I didn’t smoke; nobody in my family smoked. But breathing the air in Donora when I was little was like smoking a couple packs of cigarettes a day.” (Air pollution is linked to bipolar disorder and depression.)

Not just during those five October days in 1948, that is, but day in, day out, the way most people become sickened by bad air. The World Health Organization says outdoor air pollution contributes to more than four million deaths per year; that’s now, in the 21st century, in places such as Delhi and Beijing and Bakersfield, California, where so far neither state nor federal regulations have adequately reduced oil field and industry emissions.

“It’s thought to be the price of progress,” Davis says. “Children in certain Mexican and Chinese cities—when they draw the sky, they draw it brown.”

REMEMBER DONORA, a lapel button on display at the Smog Museum reads; the words are printed around a skull and crossbones. Brian Charlton says the button was made for the first Earth Day, in 1970, the year the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established. A few years ago he tacked a newspaper editorial to a museum bulletin board: “Climate Change Is For Real,” the headline read. And as the Western wildfires spread smoke this fall across hundreds of thousands of square miles—never in recorded history has California experienced fires like those of the last three years—Charlton says he understood that these disasters, too, are the consequence of human decisions about how we live.

Charlton’s mother-in-law was a telephone operator in 1948; she has told him about working the switchboard during the Donora Smog, trying to route distress calls. But for many years, he says, she and her husband were part of the unspoken community pact to put those five days behind them. “They knew this was a one-horse town,” Charlton says. “The horse was American Steel and Wire, and if the horse died, everything else would die.”

They were right. By the end of the 1960s, Donora’s heavy industry was gone, the huge mills dismantled, the horse dead. The reasons were economic, unrelated to toxicity; Charlton says he would have taken small satisfaction in learning of hefty cleanup costs or fines, but none were levied. An “industrial park” of the modern variety has attracted a few smaller businesses, but the town’s population remains less than half what it was in 1948. Should you hunt online for “Donora, PA,” the first image to pop up in a list of “Top sights” will probably be the Donora Smog Museum.

One last question: Did he see the photographs, that Wednesday in September, of the orange sky over San Francisco? Perhaps print out a couple to post on the bulletin board?

No, Charlton says, he did not. He read about it in the news, of course. It was hard to miss an event described as resembling the end of the world. And the atmospheric layers over San Francisco were weird that day, as it turned out; smoke from fires up north sat atop a blanket of fog, such that the worst pollution was too high be right in our faces. Instead of stinking and stinging our eyes, the way it did for weeks on end before and afterward, the smoke acted as a faraway light filter, cutting out blue light from the spectrum, flooding the daytime with orange.

“I don’t quite mean this the way it might sound,” Charlton says. “But I think I would have paid more attention if there were …” Deaths, he means. The Bay Area Air Quality Management District has broken all records for the number of unhealthy air days declared this year in the counties that encompass San Francisco, but that inversion day was by comparison one of the better ones. Absent some special respiratory sensitivity, people faced no physical danger as they wandered outdoors, squinting fearfully at the sky.

So: No doomsday. Just an unforgettable representation of one. “That’s the way I look at it,” Charlton says. “Are there deaths? Was there a tragedy involved? No? Then I say, ‘They were lucky.’ ”