A tight-knit island nation hopes to rebuild while preserving ‘the Barbudan way’

In the eastern Caribbean island of Barbuda, life is about preserving land and maintaining a close, ecologically-sound community.

I’ve had a relationship with water since before I was born.

As a young child at a barrier island off the coast of southern New Jersey, my father threw me into the cold open waters of the Atlantic, an exercise for me to find my bearings inside the waves. Watching intently, cautiously, he repeated the words that Papa, my grandfather, spoke to him: The ocean is like anything in life; Learn it’s rhythm and you’ll not only flow with it, you won’t have to work so hard to enjoy it.

My father is a sixth-generation descendant of Barbudan people. I am a seventh.

The skill of navigation, the art of catching fish, understanding the meaning of the temperature and color of the water, and so much more has been passed down to me and others through our people. And being connected to this independent, self-governing Black community, having been immersed in this culture, has been central to my identity as an African of the Americas.

It’s not surprising if you’ve not heard of Barbuda: this small, 62 square-mile island in the eastern Caribbean is the less known half of a twin island State that, along with Antigua, gained independence from England in 1981

Barbudans have kept mostly to themselves, concerned less with growing tourism than with working to preserve their land and maintain a tight-knit, ecologically-sound community of about 1,500 people.

My grandparents were born and raised in the very same village as my great-great-great-great-great grandparents. Like my father before me, I learned about my connection to the earth and her seas at the Codrington Lagoon, the wetlands that serve as the center of community life and entrepôt for our fisheries.

Barbudans are descended from West Africa and Africans of the British Isles, with many—like my family—tracing lineage back nine generations. We are fishers, navigators, farmers and artisans with a way of life that has remained largely unchanged for more than three centuries.

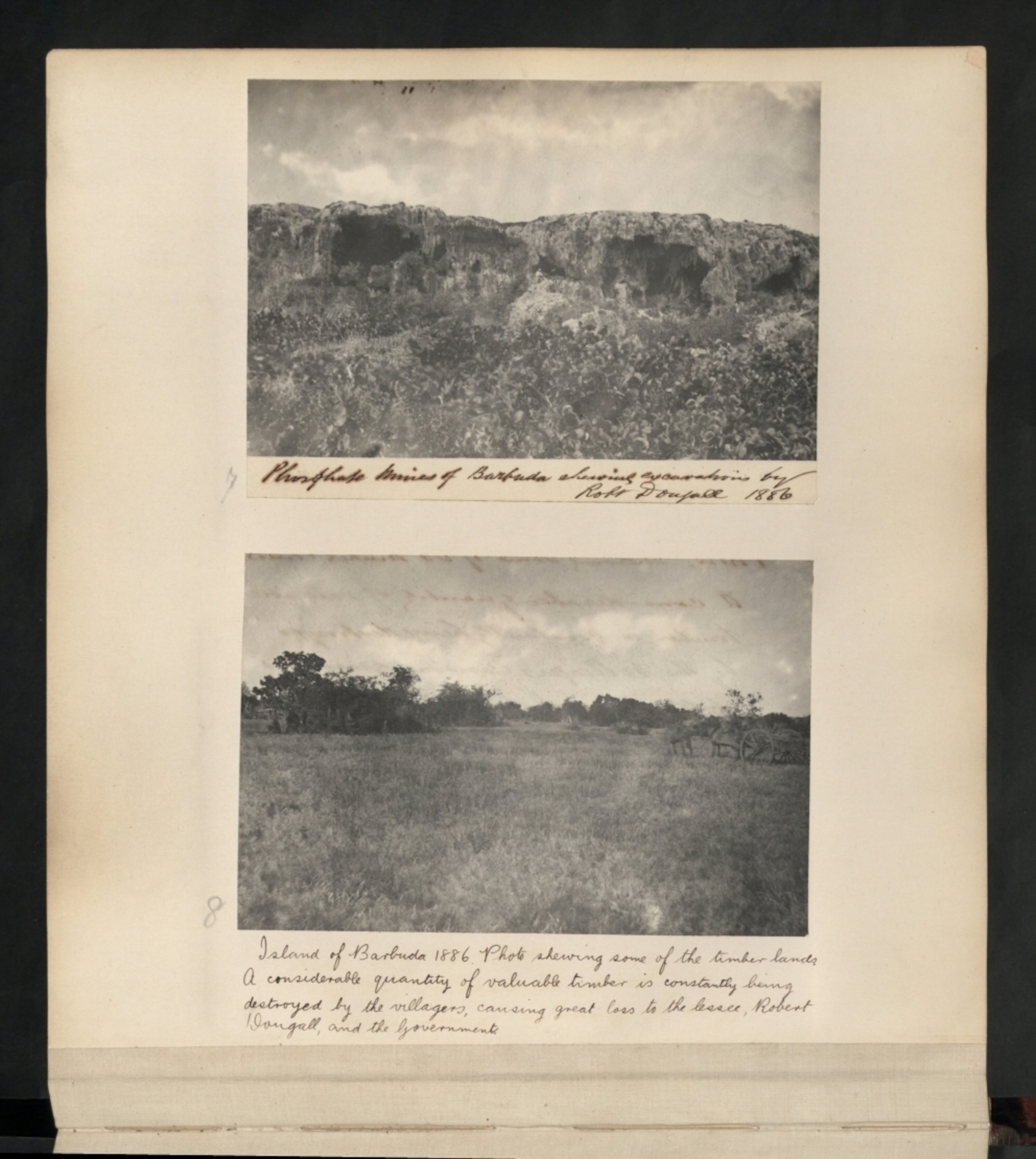

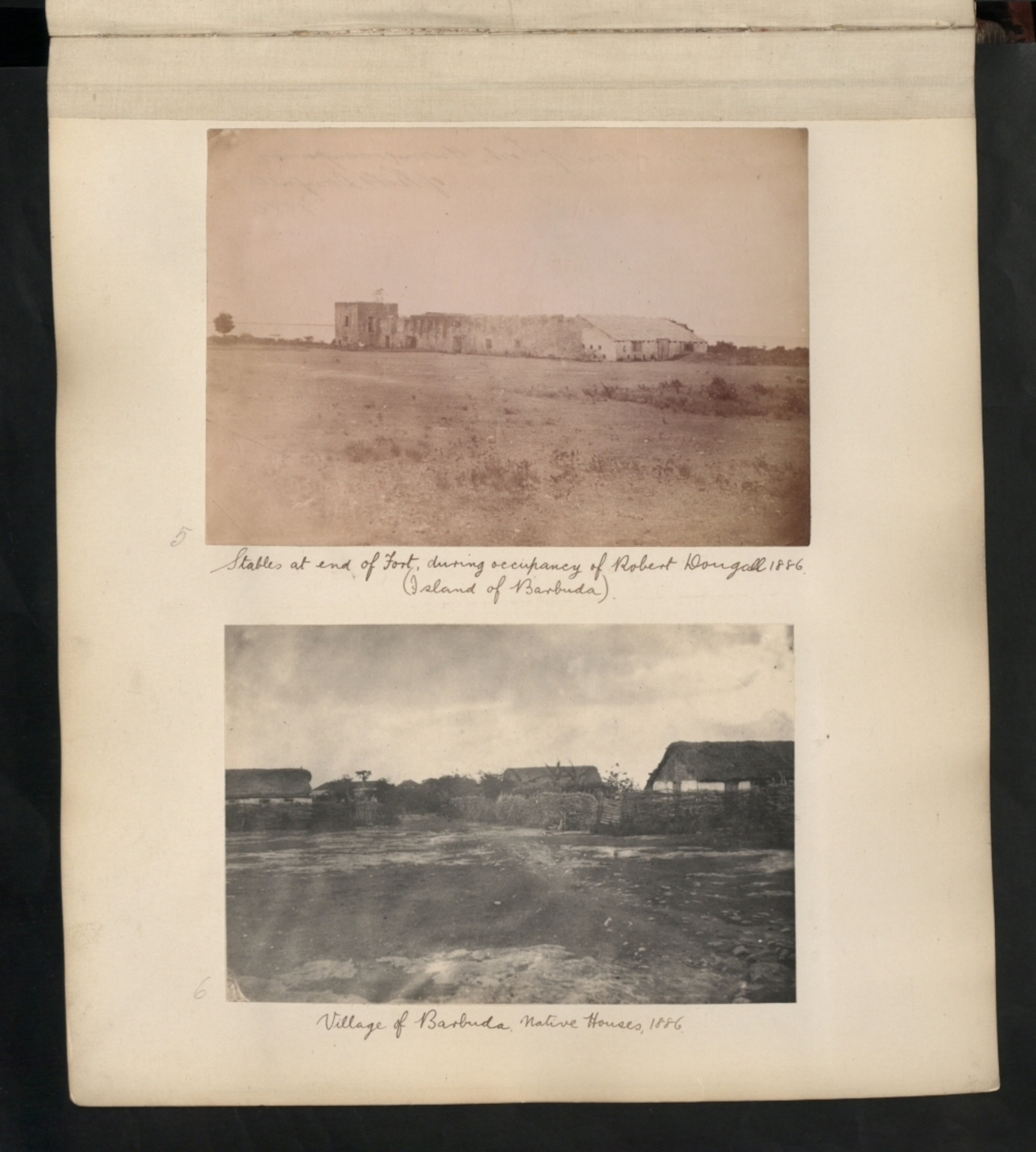

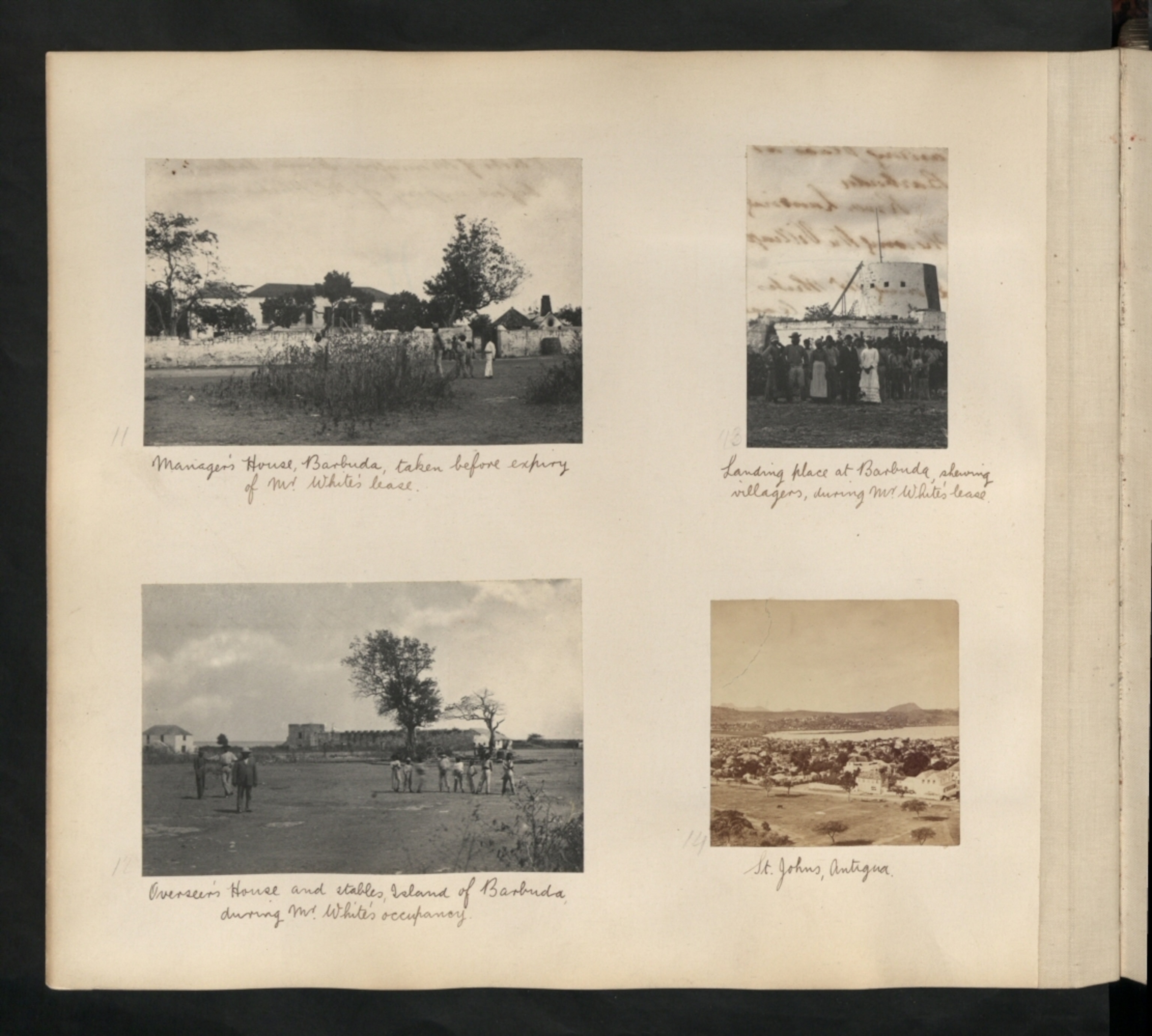

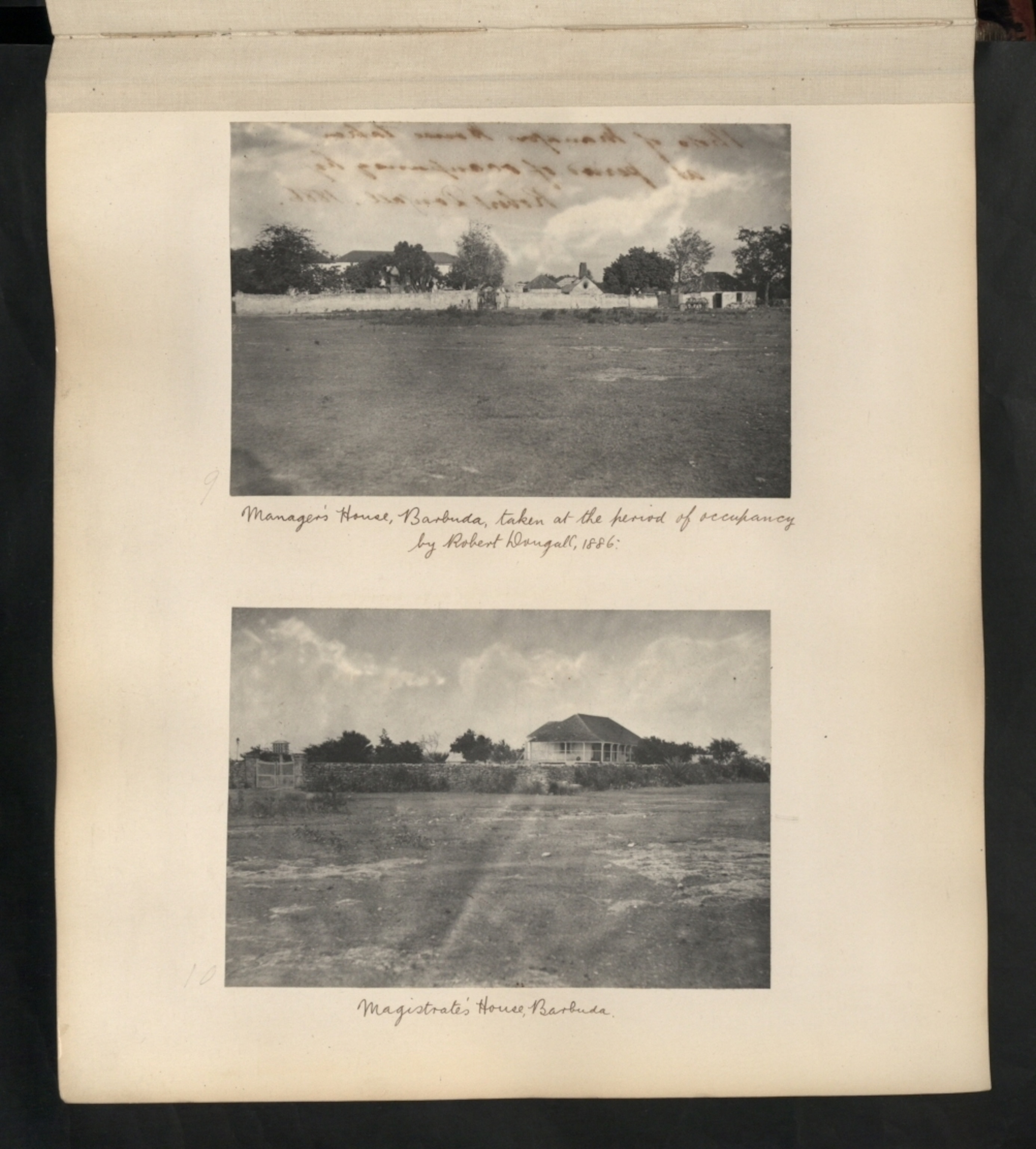

Long before the British set foot on Barbudan shores, the land was known by the Caribs, Siboney and Arawak Nations as Wa’Omoni. The presence of First Nations peoples can still be found in Barbuda today through genetics and a drawing on the interior wall of “Indian Cave” on the northeast end of the island. The British Crown claimed the island in 1685, after which Scottish brothers Christopher and John Codrington were granted an initial lease to the island by King Charles of Great Britain. This lease would later be extended by Queen Anne once she was private owner of the island. Christopher managed his sister’s plantation, Betty’s Hope, 63 kilometers away on Antigua, and had a plantation in Barbados, but was not able to create a similar plantation on Barbuda because the terrain was not conducive.

The Codringtons looked to the British Isles to import skilled laborers and indentured servants. Those who arrived on Barbuda via the main Port on Antigua were skilled as hoopers, coopers, ship wrights, metal workers, and sail makers. A number of freed Blacks who lived in Europe were drawn to the offer because in addition to wages commensurate to their level of skill, a plot of land for a domicile, a plot of land for provisions—known as “grung” even today—and supplementary rations were also offered. These laborers—plus a handful of indentured whites—were the first Barbudans. The white indentured servants departed once their debts were paid, but the Black laborers from the British Isles and later West Africa, remained, and their ancestry is connected to Barbudans today.

Barbudans are an extension of the land. It’s difficult to fully express through the written word, or even in photographs. The land in many respects is us. In a letter from June 1, 1834, Christopher Codrington described Barbudans as “one united family so attached to Barbuda that force alone or extreme drought…can alone take them from that island!”

Threats to communal well-being

Throughout the world, communal well-being has long been a feature of free Black communities, especially those that grew from resistance to the international slave trade. Jessica Gordon Nembhard, author of Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, notes that every human population in every era of human history has used and uses mutual aid, economic solidarity and cooperation to survive and thrive. She found that African Americans, like other subaltern peoples, used multiple forms of economic cooperation and collective ownership to resist enslavement and free themselves, to feed their families, to maintain land ownership, to secure affordable housing and non-predatory lending, to create decent jobs, and to keep resources recirculating in their communities.

Yet from the Gullah Geechee of the coastal American south, to the Maroons in the mountains of Jamaica, and the Garifuna of Latin and Central America, remote Black communities with their own distinct identities, language, and culture have been under relentless siege by the threat of commercial development. Unless there is international attention to quickly unify and support the rights of the Barbudan people, this independent, culturally distinct community will be destroyed.

Born in 1890, my great-grandfather James “Boatie” Harris, a Barbudan fisher and ship caulker, could navigate the dark, using only the lights from the village and the reflections from Antigua to determine the course for a boat. The fish that Boatie caught would feed his family and those in the village. Barbudan fishers decide how often they fish the lagoon and sea, know what type of fish to remove from the water, what time of year, and what size they have to be—all decisions that secure the sustainability of the fishing stock.

But fishing “the Barbudan way” is threatened by the potential shift in accordance with profitability, absent the best interests of the people. The link between people, land, resources, lifestyle and culture is based on living within the resources of the community.

To live on the island, Barbudans call on traditional knowledge to use and to protect the resources they have access to. They use their skills as fishers, hunters and farmers for food security. There is a freedom for kids to chase donkey and splash in the lagoon, and a tradition for families to camp and cook on the coastal shore during summer months. Once one person starts a fire to cook, everyone has fire to cook. This way of life has kept not only families intact but the ecology secure.

According to Cynthia Hewitt, sociologist in the political-economy tradition of world-systems theory, and director of International Comparative Labor Studies at Morehouse College: “There is an assumption that development means greater material good, and with that, greater money. But with that development is really a shift in the community well-being.”

Shift in centuries-old methods

Hewitt speaks of a shift, and for Barbuda, the introduction of development for and by non-Barbudans moves the people from cooperative owners to dependent workers. What’s more, as land and other natural resources are developed to lure tourists, the makeup of Barbudan society changes, and a delicate ecology is disrupted. These shifts can erase centuries-old methods of living with the land in the name of development.

For more than 200 years, Barbudans operated with a system of communal land ownership. In 1976, the Barbuda Local Government Act formalized the administration of communal ownership of the island with the creation of the locally-elected Barbuda Council. In 2007, the then Central Government administration in Antigua passed the Barbuda Land Act, which states that every adult Barbudan holds the land in common, with the Barbuda Council serving as administrators. It also explicitly specifies that when it comes to leasing land for major developments, consent must be obtained from a majority of the Barbudan people through an in-person vote.

A decade after the landmark legislation, Hurricane Irma tore across the island with 185 mile-per hour winds, eroding shores, and bringing level-1, 2 and 3 damage to what the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency reported was 99 percent of the infrastructure. Then, when yet another massive storm was predicted to make landfall days later, the Antigua-Barbuda central government (akin to a federal oversight body) ordered the island evacuated. When Barbudans were finally allowed to return, nearly everything had been destroyed.

A core group of Barbudans vowed to rebuild, wanting to preserve their cultural space. But it was hard to know where to start. Islanders were initially buoyed by an Antigua-Barbuda government that arranged for the swift delivery of construction equipment; but instead of repairing homes and schools and basic infrastructure (like the hospital and post office), we watched in shock as bulldozers started clearing even more trees and land to make space for a new, international airport.

While the chairman of the locally-elected Barbuda Council signed off on this deal, many say he failed to follow the mandated three-part process to obtain approval from the Barbudan people. Then, six weeks after the storm, while Barbudans were still picking through the wreckage of their homes by hand, an even larger, 650-acre development plan was approved by the Antigua-Barbuda government without involving the local Council, or the Barbudan people, in what many view as “a “land grab.”Prior to the 2017 storm, the government approved a 99-year lease to the Peace Love and Happiness (PLH) partnership, a company co-owned by billionaire businessman John Paul DeJoria, founder of Patrón tequila, for the construction of a resort and commercial village on 425 acres.

As if these actions weren’t disturbing enough, the following spring, in 2018, the central government did something that brought attention to human rights advocates worldwide: they voted to repeal the Barbuda Land Act, stripping Barbudans of our communal land rights, a central feature of our people for centuries.

Juliana Nnoko-Mewanu, a senior researcher on women and land for Human Rights Watch, authored a 2018 article on Barbuda, citing how research consistently shows that “taking away land used by communities—without due process and without adequate compensation and rehabilitation—results in serious risks to people’s rights to food, water, housing, health, and education.

“Barbuda may be small,” Nnoko-Mewanu concluded, “but the rights of its people are as important as anyone else’s.”

While some Barbudans undertook the physically grueling work of clearing broken concrete and debris from damaged homes and government buildings, others started shouldering the emotionally and financially burdensome process of fighting in court. While they have received some assistance from international groups concerned about irreparable environmental destruction, expenses outweigh the community’s ability to pay and they are relying on grassroots fundraising—all while many are still displaced and living in tents or staying with relatives on Antigua.

Hoping and praying

Renetta “Brownie” Nedd, 95, has a three-bedroom, Caribbean Sea blue home with wooden hurricane shutters that cover the four front windows and door that face the large water well known in the village as “Park Well.”

“Irma wasn’t easy. It wasn’t easy. People crying mercy. Thank God He did have mercy and He is still having mercy because if He did not have mercy we would not be here today,” Nedd said when retelling her experience after the storm. She took shelter with one of her sons while Irma battered the island. The next morning, she walked to check on her home, and did not recognize the house that she and her husband James “Hercules” Nedd updated from wood to concrete in the 1960s. She spoke of the community, and the way that homes were built and fixed on the island. “When people building a house, they have young fellas they get together. I help you, you help me, and that’s how they used to work. So I think they still have a little of that in them.”

Fifteen weeks after the storm, on Christmas morning, the village united to clear and prepare Nedd’s home for a new roof. The effort was led by Sean Charles and Mike Harris, two Barbudan retired U.S. veterans, who returned home to unite Barbudans and to prepare buildings for repairs.

As the two-year anniversary of Irma approached, Nedd said, “I have life. Where there is life, there is hope. And I’m hoping if God’s will, I may be able to get back in there. I’m hoping. I’m praying.”

She left the island in July 2019 to visit a daughter in St. Thomas. By the time she returned in December 2020, the roof was completed. Community volunteers also installed a bathroom and flooring for the house. She has since moved back in. Electricity is back on and kitchen repairs are underway.

Battle against development

Currently at least five separate lawsuits address the questions of Barbudan sovereignty, deforestation, and damage to wetlands, protected since 2005 under the RAMSAR Convention. The lawsuits question the legitimacy of recent changes to laws in order to benefit developers such as DeJoria’s PLH, Robert DeNiro’s Paradise Found, and Discovery Land Company, an Arizona-based developer. Yet while the court battles wind on, PLH has added additional development partners and expanded plans to include two mammoth private residences on about 114 acres directly inside the Codrington Lagoon National Park, the heart of Barbudan life and a hub for industry and recreation. Damage to the wetland ecosystem also continues.

In multiple public statements, PLH claims its projects are as much about “giving back to the environment” as it is about opening the island to commerce.

Yet conservation scientists unaffiliated with the island have vehemently objected to the idea that destroying protected wetlands to build a private golf course and waterfront homes is ecologically sound.

"The proposed development would deal a mortal blow to Barbuda's fisheries,” the president of the Global Coral Reef Alliance, Thomas J. Goreau, a marine biologist and biochemist wrote to fellow scientists in May 2020. “The impacts on Barbuda would be...severe [and] destroy the most important mangroves, seagrass, coral reefs, and fisheries of an entire island of fisherfolk."

Money over matter

Prime Minister Gaston Browne has repeatedly said that he wants Barbuda to “make a net positive contribution to the treasury.” Instead of acknowledging the concern for the continuance of Barbudan identity and traditions, he speaks of members of the current Barbuda Council as preventing growth, and has bluntly acknowledged his willingness to “go to Parliament to change the law to facilitate the [PLH] project.”

In 2018, he oversaw the repeal of the Barbuda Land Act of 2007 through the Crown Lands Regulation Amendment Bill of 2018, which allows for the private ownership of land by foreigners, and the enactment of The Barbuda Amendment Bill of 2018, which gives the central government the authority to approve major development on Barbuda without consultation and consent of the Barbudan people. The bill also removes the ancestral identity of Barbudans, referring to the “inhabitants” as tenants. Historically, Barbudans are defined as direct descendants of the original Barbudans that came from West Africa and the British Isles, and in order to serve on the Barbuda Council, or hold the land in common, a person had to be Barbudan. No one could purchase Barbudan identity, nor ancestral rights to the land, but the changes to the law in 2018 roll out a red carpet for privatization that removes agency from the people.

To be sure, when it comes to paying for storm repairs and upgrading the island’s infrastructure there are no easy answers. There are Barbudans who have gone to work for developers, viewing the immediate benefits of employment—the means to put food on the table—more urgently than the ideological aim of ensuring our ethnic group’s survival.

But allowing the continuation of a development plan that strips the voice of the Barbudan people all but ensures an historic, culturally unique Black ethnic group will be erased.

A legacy worth fighting for and preserving

According to Teckla Negga Melchoir, a Barbudan anthropologist and journalist, and founder of Global Forward Thinking.org, “Estimates of 100 million First Nations persons have been exterminated in the Americas since the European began 'discovering' the rest of the world. Barbudans are thought of as 'just 1,500 people on island.' Since the forced evacuation after Hurricane Irma, the local population has been decreased by at least 300. Many of whom were denied a right to return home as they were denied the right to make a living because of the illegal and draconian 'laws' passed by the current administration in Antigua, laws that facilitate foreigners who have no connection to the land, no blood in the soil and no concern for the environment, culture or people. These foreigners like those centuries ago happened upon Paradise and decided that it was up for sale and that it could be improved.”

She continues, “You ask me about development? Development for whom? Every Barbudan born in Barbuda, usually at home, has their umbilical cord buried in the yard of their house. That navel string feeds the land, roots us to the land and the land feeds us. It doesn’t matter where in the world we Barbudans go, and there are hundreds upon hundreds of us, we are emotionally, psychologically and intellectually tethered to Barbuda. ”

Prominent Black thinkers often lament how gentrification causes the loss of historic Black spaces and indigenous cultures, the destruction of Black property, the lack of generational wealth.

Barbuda’s soil survived the impact of Hurricane Irma because of the strength of the coral reefs and wetlands. Her people likewise survived the storm, but the powerful forces of economic “progress” may wipe out a homeland, a culture—an identity—once and for all.

The fate of Barbuda should rest in the hands of the Barbudan people, but now the global community is needed to recognize the distinct island culture and a people whose human rights are being violated. Without wide support in this era that the United Nations General Assembly has called “The International Decade for People of African Descent,” Barbudans who offer important direction to a collective future, are in danger of becoming just an interesting memory if we don’t recognize and respond to the urgency of now.

Barbuda is not just land. It is a Black diasporic identity. It is 1,500 lives that represent a freedom tradition, a legacy worth fighting for and preserving.

Mikki K. Harris is a documentary storyteller and multimedia journalist, and a professor at Morehouse College. She also is co-founder of the Atlanta Drone Lab and a Public Voices Fellow with The OpEd Project. Follow her on Instagram @mikkimedia.

.jpg)