The Royal Collection’s drawings by Leonardo da Vinci don't leave their protected sanctuary at Windsor Castle very often. But 2019, which marks the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death, is different. On May 24, the largest exhibition of Leonardo’s works in more than six decades debuts at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, offering visitors a unique opportunity to see ink strokes and chalk marks made in Leonardo’s own hand.

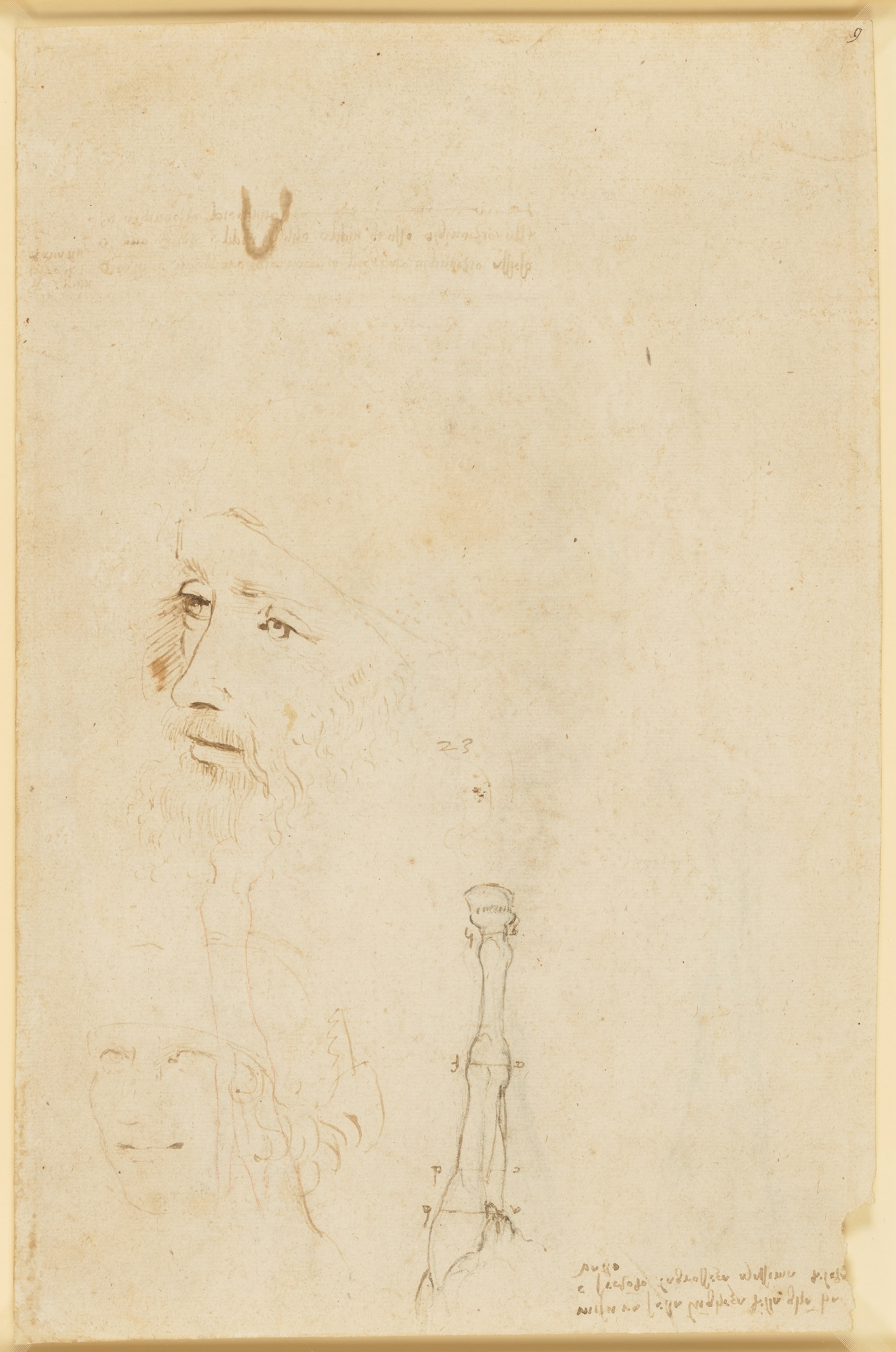

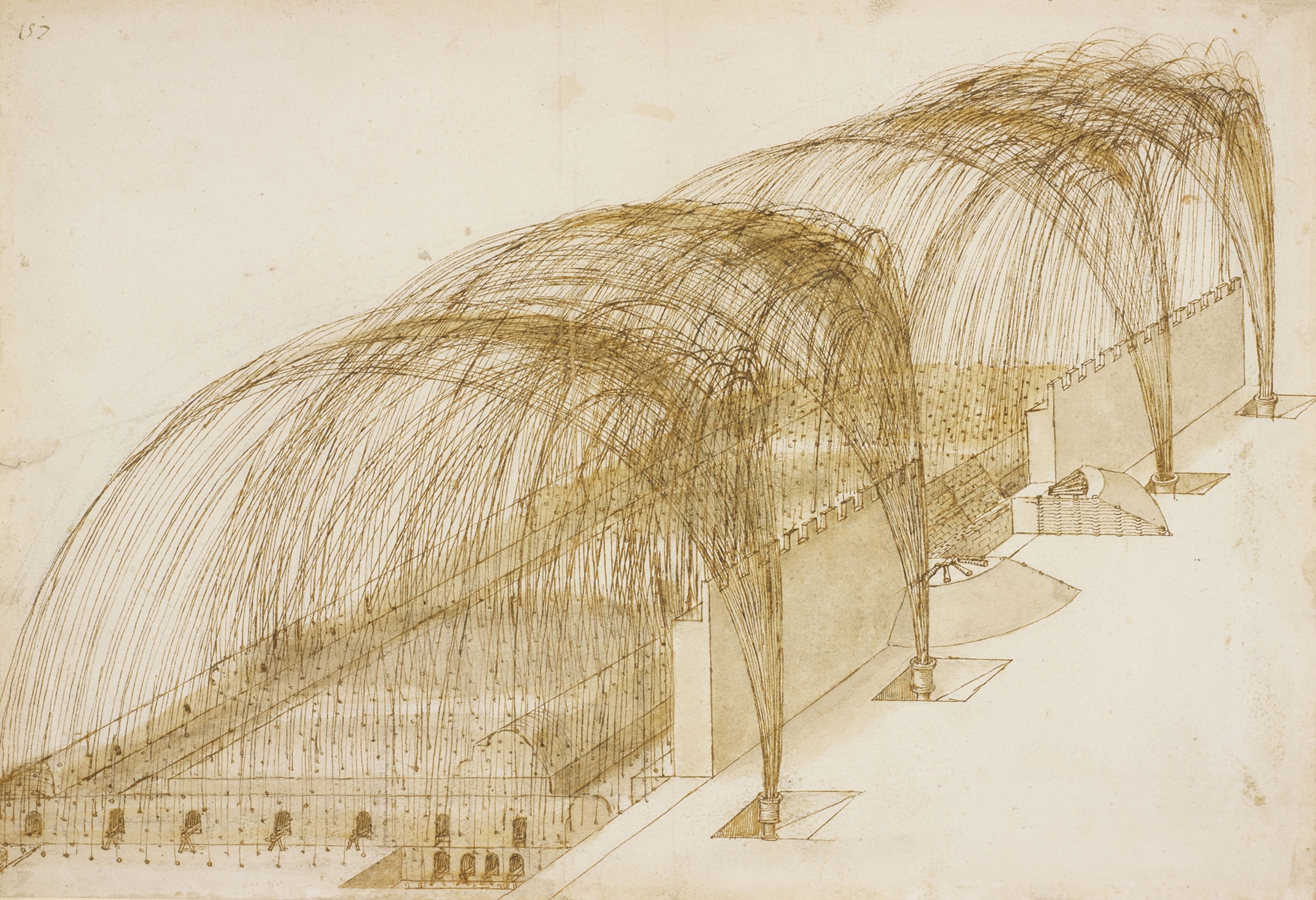

The exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing,” is comprised of some 200 drawings (about one-third of the Leonardo pages held by the Royal Collection) illuminating the artist’s expansive curiosity, subject matter, and technique. The selection include sketches for The Last Supper; designs for weaponry; and a study of hands connected to his painting, Adoration of the Magi—one of two sheets done in metalpoint so faded it is visible only under ultraviolet light. Also featured: a page containing sketches of a horse’s leg (made in preparation for one of three equestrian monuments Leonardo never completed) and an ink image of a pensive man with a wavy beard. Earlier this month, Martin Clayton, the exhibition curator and head of Prints and Drawings for the Royal Collection Trust, newly identified the portrait as a likeness of Leonardo, made by one of the artist’s assistants not long before his death.

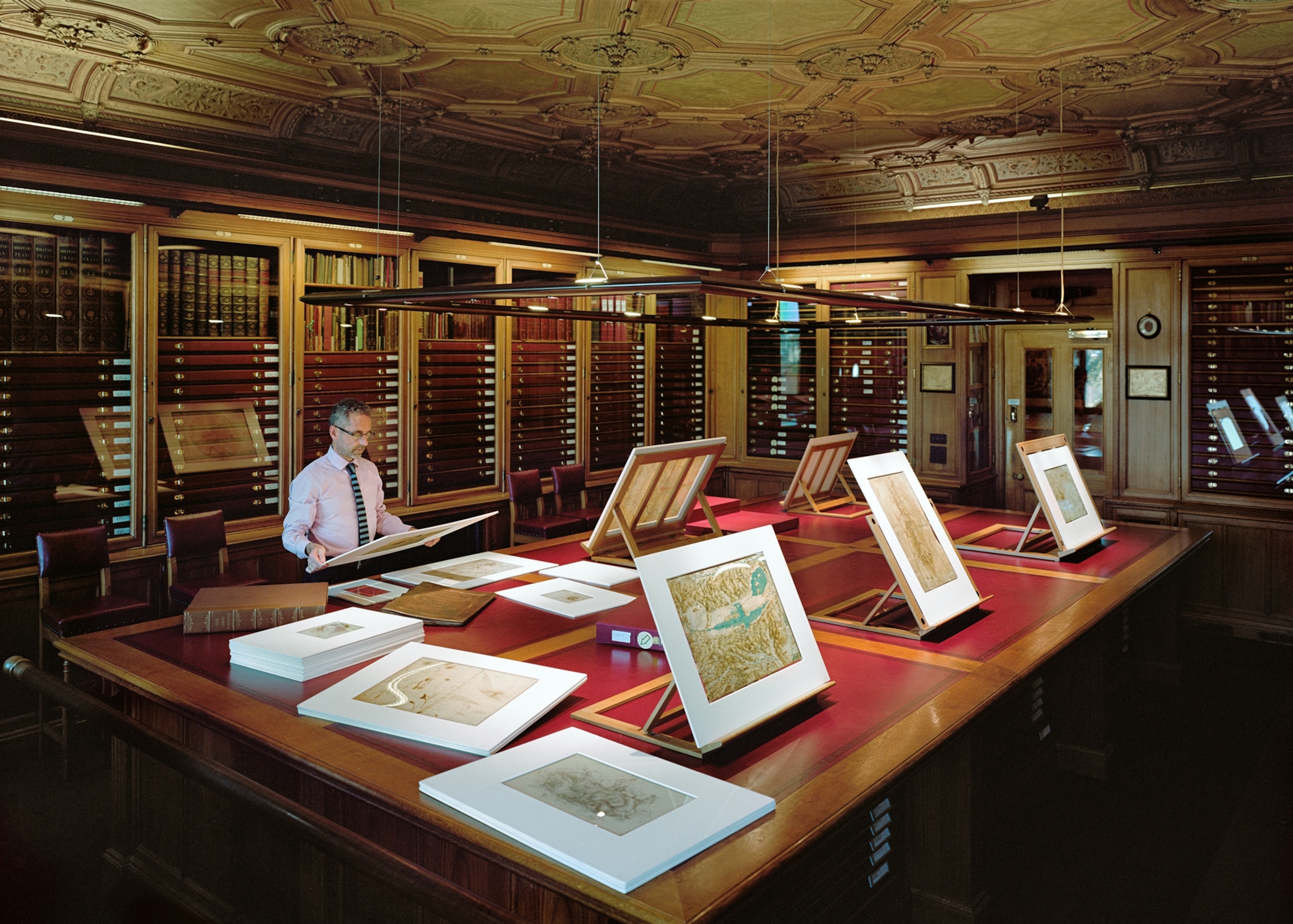

Reproductions of Leonardo’s drawings, widely accessible in books and online, lay bare his extraordinary ability to capture and visualize information. But seeing Leonardo’s artistry in its original form is a wholly different experience, a privilege I had last fall when I viewed a selection of the collection at Windsor Castle. Texture and blemishes pop from the pages and one can see the vigor with which Leonardo worked—the depth of color he explored in his paper washes and chalk, the energy of his brush marks, and his remarkable dexterity. In one drawing, he renders a one-inch study of the Leda in just a scattering of pen and ink marks; in another, he portrays the drapery on Madonna’s arm, a study for The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, in breathtaking transparency using red and black chalk strokes heighted in white. “No reproduction,” Clayton says, “captures the range of tones and the subtlety and the life of these drawings.”

Nor can a reproduction compare to the immediacy of the originals, which lures viewers into a personal rapport with the artist. You feel connected. That relationship, along with the artist’s tireless effort to make sense of everything around him, humanizes Leonardo’s genius. His prowess evolved through hatch marks, scribbles, and shading to understand astronomy, architecture, anatomy and so many other fields of study. On the same page as his famed drawing of a fetus in a breech position in the womb, smaller sketches show the artist’s efforts to work out the biology of the placenta and the physics of how a curled up baby turns headfirst at birth. His drawings were his own experiments. “He’s playing around with his imagination,” Clayton says.

One of the most striking aspects of Leonardo’s originals is the handiwork left behind by those who inherited his creations. The artist bequeathed his drawings to Francesco Melzi, his devoted student, who received them after Leonardo’s death, on May 2, 1519, and held onto them for some 50 years. Melzi attempted to categorize portions of his teacher’s subject material, Clayton says, which is often scattered incomprehensibly from one page to the next. He marked Leonardo’s drapery, map and deluge drawings with consecutive numbers in an effort to give them some order. In certain cases, Melzi even cut out profiles and small figures from different pages as he endeavored to unite similar themes, including Leonardo’s famed series of “grotesques,” which depict unpleasant human faces with oversized jutting chins and bulbous lips.

During my visit, Clayton held up one of these pages to show me the end result. “You have a drawing something like this, where Melzi had cut bits out there,” he said, pointing to angular gaps at the top and on the side of the paper. The missing chunks only add to an already convoluted array of disparate subjects on the front and back of the paper—a young man’s profile; a decorative dress; a hydraulic device; an esophagus and stomach.

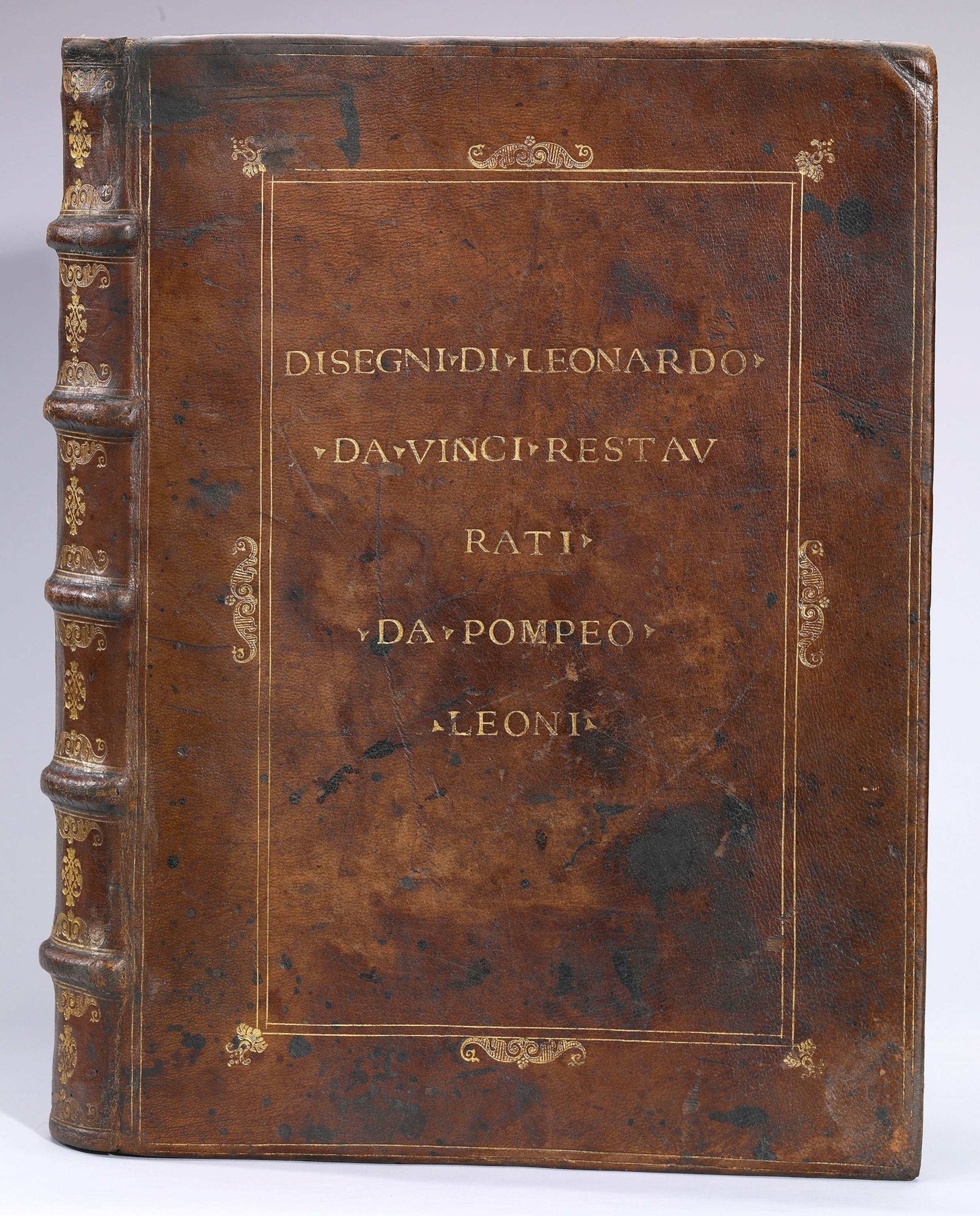

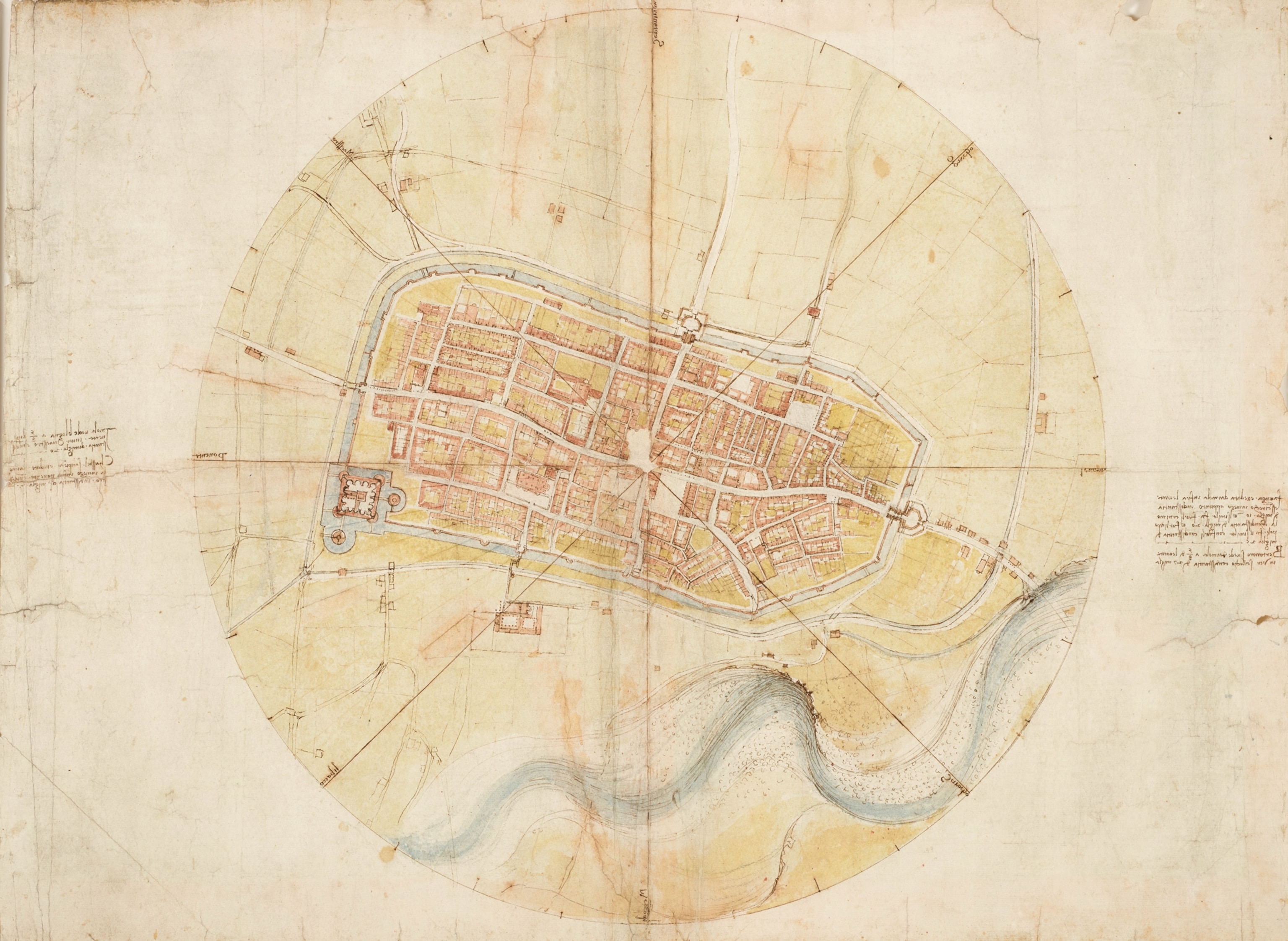

Other alterations continued after Melzi’s death, around the year 1570. The sculptor Pompeo Leoni acquired Leonardo’s drawings and subsequently bound them into at least two albums, one of which landed in the Royal Collection. Cramming some 600 drawings into a single leather volume containing just 234 folios was clearly challenging. Leonardo’s plan of the northern Italian town of Imola bears testimony to this: crease marks running horizontally and vertically reveal where it was folded into four and a small hole has been worn through the center of the paper.

The artist’s exquisite map of the Valdichiana, in southern Tuscany, contains other idiosyncrasies. The writing on the map reads conventionally from left to right rather than right to left, Leonardo’s distinctive mirror writing, suggesting it was prepared for a professional commission—not for the artist himself, which was more typical of his other drawings, Clayton says. The back of the page shows a crudely drawn profile (not one of Leonardo’s, Clayton assured me) as well as remnants of red sealing wax, which was likely used to adhere the map to a board for presentation. “The archaeology of these drawings is fascinating,” he says.

Whether torn at the edges or marked with pulp, stains or watermarks, every one of Leonardo’s originals contains its own centuries-old residue. Seeing all of this up close is a singular experience and this year provides a variety of opportunities to do so. Among other exhibitions, more than 50 of Leonardo works are currently on show at The Royal Museums of Turin, including his “Codex on the Flight of Birds,” and the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice is displaying Leonardo’s celebrated “Vitruvian Man,” along with two dozen other drawings.

The Queen’s Gallery exhibition at Buckingham Palace, which runs through October 13, is bound to draw large crowds. Already this year, 12 smaller displays of the Royal Collection’s drawings at venues across the United Kingdom drew one million visitors—far exceeding expectations. The final phase, after London, will take place at the Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, Scotland, where a group of 80 drawings will be exhibited from late November to mid-March 2020.

Taken as a whole, Leonardo’s drawings are a testament to the artist’s indefatigable passion for learning. “What Leonardo can teach us today is that by looking well beyond your own discipline, you get inspiration,” Clayton says, “You get a sense of possibility.” A way of seeing that can ignite wonder in us all.